I noticed him but he chose not to notice me. After he had dropped his mobile phone on the floor for the third time, he realised that he had to say something.

I noticed him but he chose not to notice me. After he had dropped his mobile phone on the floor for the third time, he realised that he had to say something.

Wiry little fucker—blonde hair, tattoos. Apologies to the Arctic Monkeys. The boy’s a slag, the best you’ve ever had. The sex was brutal, violent—and it was wonderful. But it was only a dream. I woke up, realised none of it had happened… and now I can’t look him in the face anymore.

Little boy, full of excitement, runs down the hill, his parents far behind. His legs go faster than they can carry him and I fear he will fall. But he is too young to recognise danger and is safe for now. He heads to the sea, with its tiny cottages with smoking chimneys, fishing boats, and ice cream. His parents smile as he tries to hurry them along. This is a moment that this little boy may or may not remember. But when he is old, and his parents are long dead, he might sit where I am now, and watch other little boys doing the same as he did, and know that he had a wonderful childhood.

I saw you several times and you ignored me. Why do I remember that? It was because I thought you were handsome. But ignorance turned into friendship, and I hadn’t realised how generous you were. And that generosity came from Robin Hood. Steal from the wealthy, and give it to others. I met you tonight, fresh faced and smart, a tap on the shoulder, a cheeky wink, and you gave me a bottle of beer. I doubted that you had ever ignored me.

The concrete city, where unruly boys roam, and life moves dangerously fast. The golden boy’s halo slips and falls to the ground like a tin can dropped from the balcony above. It hits the pavement and breaks and the blissful boy becomes the common threat.

The sweetness is in the boy. It’s there for all to see. JJ asks him how old he is, and he replies that he is eighteen. Such a young boy to be working in an uptight environment. But when he talks, Oliver looks JJ straight in the eye, but there is wariness.

“Who are you waiting for?” “Nobody.” He looks to the floor. “Why are you still here?” “I don’t know.” And Oliver clutches the skateboard to his chest. “I guess I’ll get going,” and Oliver walks into the dark. A small, lonely figure.

And then Caitland rushes out and asks where Oliver is and sees him standing alone at the edge of the road. She rushes towards him and puts her arms around him. He drops the skateboard, and they embrace, but this is no romance, because it is a comforting hug that suggests that Oliver is not in a good place.

I’ve been watching in silence, and I tell JJ that we need to go. We get in the car and JJ says that Oliver reminds him of me. Cute and polite. I’m flattered.

As we drive away, I see them huddled together under a streetlight and it looks like Oliver is crying. I feel sad and when I get home, I write a message.

“Hey Oliver. There was something wrong with you and I talked to JJ, and he thought the same too. A bit of anger in those eyes. Hope all is ok with you. I’ve got a lifetime experience of fucking up, so I’m well qualified if you need a chat.”

I never send the message.

If I’d been a member of the Brat Pack, I would have wanted to have been Rob Lowe. But I was more like Andrew McCarthy.

He wasn’t handsome, nor was he a good actor. I wasn’t handsome either, or ever been an actor.

Underneath that cute shyness he was an outsider, not liked by his contemporaries, and he was resentful, and probably not a nice person.

“Early on in The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald describes the character Tom Buchanan as a ‘national figure in a way, one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savours of anti-climax.’”

Now we know the truth.

McCarthy thought he could deal with fame, but wasn’t able to, and lived by the bottle. And this meant that once he’d peaked at a young age it was downhill. And then, by his own choice, it ended.

“Maybe you didn’t want it,” Alec Baldwin said to him on the Here’s the Thing podcast without realising he’d come closer to the core than McCarthy ever had.

I’m not sure I liked him after reading this, but he writes clearly and honestly, and afterwards I realised that we were alike after all.

He might not have been a nice person, but I suspect he might be now.

He was called Fabrício and said he came from Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro. It was the tattoo I noticed first, a bird on his neck, and I was suspicious of guys who had tattoos. We sat drinking beer at the counter. The barman cleaned up. The night was ending.

“What is your name?” “Where are you from?” “What do you do?” “What are you doing here?”

Fabrício wanted to talk, but I was tired, and came across as being rude.

Tito’s Vodka. Corn Whiskey. Pama Pomegranate Liqueur. RumChata. Rye Whiskey. Southern Comfort. Tennessee Whiskey. Jack Daniel’s. Bourbon.

I read the labels on the bottles behind the bar.

In the mirror I saw two guys. And I found a thousand things wrong with me, but only the bird on Fabrício’s neck.

“I’m gonna make a change, for once in my life. It’s gonna feel real good. Gonna make a difference. Gonna make it right.”

Fabrício gently sang the opening verse from Man in the Mirror. It was a sweet voice. I could not sing.

I looked in the reflection and noticed him looking at me. It reminded me of a scene in Rebel Without a Cause where Plato looks at Jim with a look of adoration. A coded declaration of love. Gay desire.

“I’m starting with the man in the mirror. I’m asking him to change his ways. And no message could have been any clearer. If they wanna make the world a better place, take a look at yourself, and then make a change.”

That was it. The first time for me. We had met in a hotel bar in Fort Lauderdale and ended up making love behind a stack of deck chairs on the beach, protected by the roar of the sea, and waiting for the cop with a torch and gun.

I was browsing vintage books and had just picked up an Oliver Messel biography. I was debating whether to buy it or not. The aisles were narrow and as far as I was aware there was nobody else in the tiny shop. But there was. And I was conscious that somebody had stuck their head around the corner. It was a boy, probably in his late teens, who held a book in his hand. He scanned the rows of old Daphne Du Maurier novels, didn’t see what he wanted, and retreated. I could hear him presenting his book to the shopkeeper. “I’m happy I’ve got what I wanted.” A bell rang above the door, and he was gone. I decided to buy the Oliver Messel book and left carrying it under my arm.

That might have been the end of the story had it not been for me wanting a cigarette. I walked the short distance to the quayside, found a bench, and smoked. It was a sunny day without the usual tourists, and I watched a cargo ship sail into harbour and up-river towards the China Clay docks.

The ship sailed past, and I noticed the boy from the bookshop. He leant over the harbour wall looking at the boats below. He drank from a takeaway coffee cup and placed it alongside his book.

He turned around, smiled, grabbed his possessions, and came over to sit beside me.

“Hasn’t anybody told you that smoking is bad for you?”

“I’m too young to worry,” I replied, “And too young for anybody to notice.”

I blew smoke over him, and he waved it away.

“I saw you in the bookshop. What did you buy?” I showed him the Messel book. He nodded in approval.

“What did you get?” He turned the cover to me, and it was a biography about Alfred Munnings.

“I expected to see Du Maurier,” I told him.

“I live in a house where Daphne Du Maurier once lived,” he stated. “My bedroom is where she slept. And when I’m half asleep I swear she visits and looks over me. I think she’s my guardian angel.” He paused. “So here we are. A pair of teenagers reading books that we shouldn’t be reading until we’re fifty.”

The boy was right. Two old heads on young shoulders. I liked him.

A mop of thick black hair, blue eyes, milk bottle complexion, and not particularly handsome. But when he smiled, he had perfect white teeth, and his narrow face lit up and he was strangely attractive. I guessed from his voice that he was local. He stretched his legs out, clutched the book to his chest, and gazed out to sea.

“I’m seventeen,” he said, “And one day I’ll be old, and I’ll be sitting here on this bench talking to a stranger, who’ll also be an old man.”

“I’m nineteen,” I told him, “And that stranger might be me, and I’ll remember the day we met when we were young.”

“And we’ll talk about regrets, and the things we never achieved, and how life became intolerable, and how we wished we were young again.”

The boy was called Samuel and the son of a wealthy mother, no father, who lived by the river, and he told me that he would grow up to be an intellectual.

He crossed his legs and revealed a patch of white skin above his ankle. He sensed my stare and allowed the leg of his jeans to ride further up to show tiny wisps of dark hair.

“I’m Zack,” I told him. “I live with my girlfriend in a bedsit in North London. No history. No ghosts. We’re students struggling to make a life together, and we study theatre design.”

“And that’s why you bought a book about Oliver Messel,” he confirmed. He looked at the cover that featured a self-portrait of Messel when he was the same age I was now. “He was handsome.”

“But he got older,” I said, “and less handsome, but incredibly successful.”

“I think I’m gay,” the boy said matter of fact. Why did he say that? Does he think I am too? Did I not say I had a girlfriend?

My silence was conspicuous. He looked me in the eye. “That’s what they say at college.”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“Because I’ve never told anybody before. And you seemed to be the right person I could tell.”

“I’m not gay. What qualifies me to understand?”

He hadn’t taken his eyes off me. Pleading eyes that hoped for an answer he wanted to hear.

I thought of Kirsty, my first love, the girl who I shared everything with. Then I recalled the argument we’d had earlier, when she’d accused me of not being interested in her. By that, I discovered, she wanted me to take endless photographs of her for that Instagram feed of five thousand followers. I left to walk the streets.

And then Samuel appeared, and in a few minutes, I would walk away and never see him again.

“I didn’t say you were gay,” he said dejectedly. “I just wanted to tell somebody. It’s a big thing because what they say is probably true. I do like other boys.”

“And are they fine with that?”

“Some are. Some aren’t. Mostly they tease.”

“Does that bother you?”

“Not really, but sometimes it makes me sad. There are times when I meet somebody I like, and I want to explode because I’m afraid to say anything.” He took his eyes off me and looked across the water. “It’s a mind game. Instead of coming right out and saying that I like them, I drop subtle hints that never get picked up on.” He fumbled with his coffee cup. “And if I did say anything, I’m afraid of what the outcome would be.”

“The fear of rejection?”

“Yes, and what would happen if anybody found out.”

Nobody had ever confided in me. It was a strange feeling. Somebody I had never met before was pouring his heart out to a stranger. This was somebody else’s life, not mine. It meant nothing. And yet, I sat there feeling uneasy about it all. I didn’t know what to say, and we sat in silence, clutching our old books

“I know. Let’s go for a walk. I want to show you something.”

It should not have happened like it did. Samuel guided me along narrow Fore Street, its shops, cafes, and restaurants, doing scant off-season business. People hindered us as they walked side-by-side, oblivious to their surroundings. I followed him. He was smaller than I thought, but confident in his stride.

Shops gave way to holiday cottages, and Samuel stopped and waited for me to catch up. He had a mischievous look about him, swept a hand through his thick hair, and using the Munnings book as a guide, pointed down a narrow alleyway. It looked to be a dead-end, but I followed him down the cobblestones to the point where he disappeared through a gap to the right. It led into a tiny courtyard, surrounded by four stone walls. At one end was a rickety paint-worn door secured by a padlock. Samuel found a key in his pocket, unlocked it, and beckoned me through.

We were on a small stone terrace that looked over the harbour. The sea was azure blue. Small boats bobbed on their anchor. He closed the door and I realised we were completely hidden.

“This is my secret place,” he told me. “Nobody comes here, all but forgotten, except I found it and claimed it as my own.”

It was beautiful. The afternoon sun glinted off the water and cast rippling shadows on the wall. Water lapped against the granite. It was blissfully quiet, except for the faraway voices of fishermen and boatmen, and the put-put of a passing motorboat.

“This is where I come to be alone, read, and to dream.”

The words were perfect for THAT moment. Many years later, when I started writing plays, I would use that same line and remember where they came from. No matter how many times I heard it, spoken by the finest actors, it was never right. Never again would it be THAT time, THAT place, THAT person.

Samuel sat on the warm stone, pulled his shoes and socks off, then rolled up the legs of his jeans. He sat on the edge and dipped his toes in the water. His gaze was fixed on the opposite bank where another life existed. “One day I’ll be a writer, and I’ll describe this place.”

I stacked the two books on top of one another and sat cross-legged beside him.

“This is the place where you come to hide?”

“There’s no place to hide because the world is on the other side of that door. One day, I’ll have to face it.”

“It’s not a bad world,” I told him. “It’s difficult, but it’s a life worth living.”

And then I thought of Kirsty and felt guilt. I wasn’t sure why. Was it because I had been too hard on her? Was it because I had left her sobbing in the holiday flat? Then I realised it was neither. I was glad at what I said.

I thought of the time I got drunk and slept with another girl. I fell asleep and nothing happened, but afterwards I was full of remorse.

“You’ve gone very quiet,” said Samuel. “I’m starting to think that bringing you here was a mistake.”

“Far from it,” I replied. “I’m glad I came. I’m just trying to absorb everything.”

“Like what?”

“Less than half an hour ago, I’d never met you. I saw you in a bookshop, had a conversation on a bench, and now I’m here in this secluded spot by the sea.”

“No regrets?”

“None at all,” I assured him.

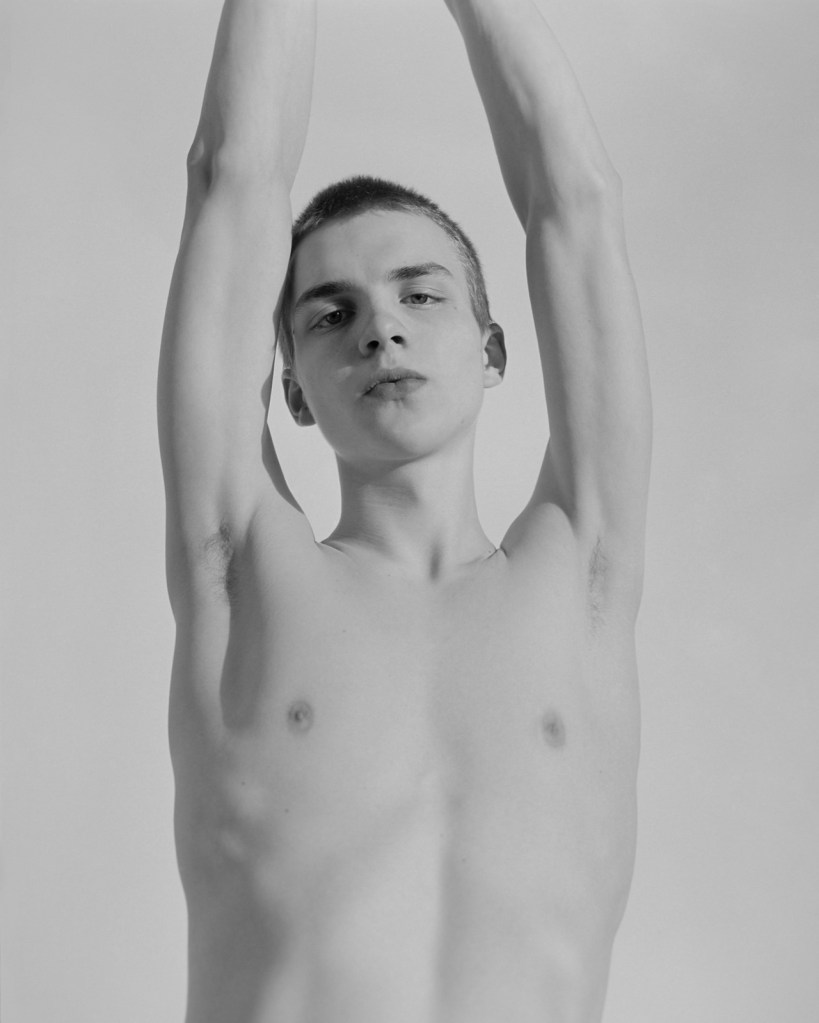

“It’s warm.” Samuel slipped off his tee-shirt and revealed his slender lily-white body. He was still a boy, not quite filled out, with a smooth chest and skinny arms. He leant back on both hands and put his face to the sun.

“There’s only two years between us, but somehow you seem a lot older than me.”

“Two years is a long time. I remember being seventeen and it seems a lifetime ago. You’ll finish college, probably go to university, because you seem clever, and suddenly you’ll be the same age as me.”

He laughed. “My mother says I’ll never leave Cornwall. I’m her spoiled child and she thinks I’ll grow up, get married, have kids, and then we’ll all move in and live with her.”

“Does she know about you and… other boys?”

“She’s too absorbed in her work and committees to notice anything. That’s a good thing because you haven’t seen her when she goes into meltdown. She calls me queer, but not in THAT sense.”

He flashed a smile, and I realised that I’d been staring at him. And then that strange feeling returned. If it wasn’t guilt, then what was it? My head was hazy, and my stomach twitched.

“I have something for you.” He jumped up and walked to the corner of the small jetty. Water splashed from his feet, and he trailed delicate footprints across the warm stone. He crouched in the corner, pulled away part of the stonework, and reached inside. He extracted a bottle of cheap red wine, almost full, and held it aloft.

He unscrewed the top, took a long swig, and passed it to me. Then he sat back down beside me.

“Remember this moment, because I am going to do something that you’ll never forget”

Samuel kissed me on the cheek, and then I allowed him to kiss me on the mouth, and it felt good.

He was right. I never forgot that moment. And now, years later, as I look back, it changed everything.

Afterwards, I never saw or heard from Samuel again.

But I recently had an appointment in London and was smoking with my agent outside Starbucks. He told me that a client of his was working on a new biography about Oliver Messel.

And then a handsome guy, who looked vaguely familiar, walked past, and shook his head. “Hasn’t anybody told you that smoking is bad for you?” And for a moment, I was back on a secret stone jetty, beside the river, one sunny afternoon.

It is a cold September afternoon and not the weather to be wearing shorts and little else. But Leo is different. We don’t know his real name, but we shall call him that, because he looks like he should be called Leo.

Leo is in a small supermarket, and he looks about fifteen or sixteen. He has a shaved head, mischievous eyes, and boyish stubble. He will never be considered good-looking until he abandons that pursuit of chaviness.

‘I am Leo, and I will shock you.’

The only signs of manhood are his scrubby hairy legs. His slender torso is pale, smooth, and scrawny. Despite the cold, there are beads of sweat across his chest, and if you stand close enough, you’ll recognise that faint smell of a teenage boy.

Leo is quick, and if you were to fight him, he would be incredibly slippy.

He has no money, and as he brushes past old women, he thinks about stealing a packet of crisps, or a chocolate bar, but there is nowhere to hide them.

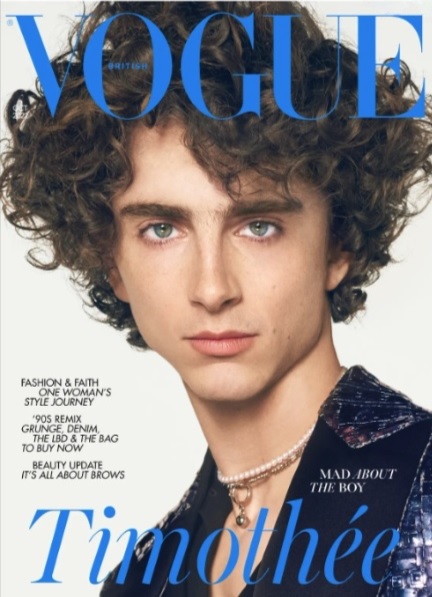

When Leo reaches the newsstand, something catches his eye. He stands and stares, and somebody looks straight back at him.

Leo studies the fox-like face on the front cover of Vogue magazine. He looks at the gentle lips, that noble nose, and green sex eyes, then notices that the eyebrows have been carefully plucked. Most of all, he likes the thick black curly hair. Leo thinks that he has never seen a man look so handsome.

Leo stares too long and realises that he’s put his hand down the front of his shorts like gangsta boys do.

“You battyboy, bro?” says a gangsta boy voice behind him. Carter, dressed in school uniform, grins over Leo’s shoulder.

Leo clenches his fists and swings around.

“I ain’t no battyboy, bro,” challenges Leo. And in his deepest gangsta boy voice, tells Carter. “I swear I will bang you if you ever say that again!”