I have a feeling that something bad might happen. It makes me nervous. Like when you want to have a shit but you’re worried because the drains keep backing up.

I have a feeling that something bad might happen. It makes me nervous. Like when you want to have a shit but you’re worried because the drains keep backing up.

The first time Brodie and Archie met was not under the best of circumstances.

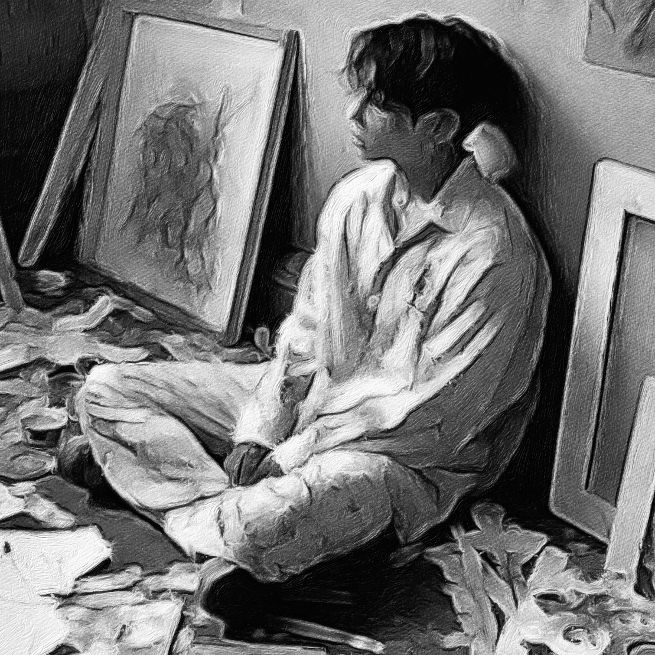

It was a Friday afternoon beneath the Miller Theatre on West 51st Street. Brodie – hi-viz vest zipped to the throat – stood amid abandoned scaffolding, photographing stress fractures in the concrete. The air was dense with dust, old and mineral, as though the building itself were exhaling.

A figure emerged at the far end of the tunnel and walked towards him.

Brodie lowered the camera. He waited until the young man was close enough to see properly, then snapped, “What are you doing here? This is a restricted area. Turn around and go back the way you came.”

“I’m sorry,” the young man said. He spoke with an English accent, careful, almost courteous. “I didn’t realise. What was this tunnel used for?”

“The other side of that wall is backstage,” Brodie replied. “Probably for actors crossing beneath the stage. But there’s no time for questions. It’s unsafe down here. The roof could come down at any moment.”

It was an exaggeration. But saying it gave him a small, illicit thrill – authority borrowed from the place.

The young man hesitated. He had floppy brown hair, eyes dark and inquisitive despite the rebuke. “What are you doing?”

“I’m inspecting the structure,” Brodie said. “Everything looks glitzy up there. Down here it’s rot and age.” He paused. “You still haven’t explained why you’re trespassing.”

“I was just exploring.”

“Explore somewhere else.”

The young man’s shoulders dropped. As he turned, he fumbled the folder under his arm; papers spilled across the dusty floor.

“Shit – sorry. My script.”

Something softened in Brodie then, too late to retract the sharpness he’d already spent.

The second time they met was in the staffroom.

Brodie was entering notes on his laptop when the door burst open and a tide of people flooded in, loud with laughter, trailing the smell of coffee and citrus wipes. Lunch packs appeared: protein bars, yogurt, hummus, cut vegetables. Actors, Brodie thought, irritated beyond reason.

Michael wanted renovation proposals by Monday. Concentration felt impossible.

Then he saw him – the boy from the tunnel – laughing with the others, sleeves pushed up, script tucked under his arm as if it were a talisman.

Of course.

On their way out, the young man stopped at Brodie’s table. “I’m Archie,” he said, holding out his hand. His eyes lingered, dark and unguarded. “I think we got off on the wrong foot.”

Brodie hesitated, then took it. The contact was brief, oddly charged. “I’m Brodie. Forget about it. Just – stay out of the tunnel.”

Archie smiled, chastened and amused all at once.

After that, Brodie thought about him more than he liked to admit.

He knew he could be abrupt, inflated by his own sense of usefulness. Actors irritated him on principle. But Archie – English, polite, quietly intense – had unsettled him.

Late one night, Brodie searched the Playbill bios. Archie was a rising star: television work, the National Theatre, lead roles in the West End, now a Broadway debut.

Impressive.

What Brodie didn’t know was that Archie had been searching too. He’d asked about the surveys, about the renovation. He found the company. He found Brodie’s photograph.

Hazel eyes. Skin warm-toned, as if lit from inside. A face shaped by movement rather than posing.

Tasty, Archie thought, surprised by his own boldness.

Two years later.

Archie slipped out of the Walter Kerr Theatre the moment the curtain fell on Chatterton. No shower. No linger. Wool coat, beanie, scarf pulled high. He moved fast, before the autograph hunters gathered.

Outside, Broadway surged and glittered – yellow cabs, steam vents, neon, voices colliding. It still thrilled him. It always did. A world away from Buckinghamshire.

At the apartment, Brodie checked the clock: 10:30. Any minute now.

The flowers were arranged just so. Archie liked flowers. Brodie liked that Archie liked them.

When the door opened, relief moved through him like a current.

Tea was requested. Always tea. Archie shed the night – coat, scarf, public self – and collapsed onto the sofa. He spoke about the show, about the line he’d missed. Brodie stroked his hair, grounding him.

Later, Fleet Foxes floated from the bathroom. Steam curled beneath the door.

Brodie knew the routine by heart. He would collect the clothes, note the forgotten boxers, breathe in the faint, intimate salt of them – something human beneath the polish. It embarrassed him how much that scent moved him.

Archie emerged clean and fragrant: Le Labo, Dior and mint. Blue silk pyjamas. He smiled like someone stepping into safety.

They ate together. They watched television under the blanket Archie’s grandmother had made. Archie pressed close, smaller than he seemed onstage, all softness and thoughtfulness and unspoken worry.

Sometimes Brodie felt the weight of what he was not allowed to be – unseen, untagged, absent from photographs. Invisible by design. But here, in this private room, their bodies fit without explanation. The most erotic moments were those that could not be shared publicly.

Brodie was Archie’s shelter. Archie was Brodie’s undoing.

Brodie had watched hundreds of videos of Archie on YouTube, moments in which he appeared entirely at ease – charming interviewers, holding eye contact, listening with an attentiveness that felt generous rather than rehearsed.

His answers were always articulate, delivered with that unmistakable smile. But Brodie could see what others missed.

The exposure beneath the polish. The small betrayals of nerves: the way Archie’s smile lingered a fraction too long; the absent-minded stroking of his own arm as he spoke; the slow, circular massaging of each finger; the hand lifting to his hair, not to adjust it, but to reassure himself it was still there.

These gestures were invisible to the audience, but to Brodie they were intimate, almost confessional – proof that the confidence was something Archie stepped into, not something he owned.

Thomas Chatterton had been an ideal role for Archie. The eighteenth-century poet – celebrated as the marvellous boy for his precocious brilliance and dead at seventeen – had been reimagined as the subject of a hugely successful Broadway musical.

In his twenties, Archie might once have been considered too old for the part, but his fine, boyish beauty dissolved any such doubt. Night after night, he stepped into Chatterton with such ease that the distinction between role and actor began to blur.

To the audience, he seemed timeless, suspended in youth and promise. To Brodie, there was something quietly unsettling in this devotion – the way Archie gave himself over to a boy who never lived long enough to be disappointed by what came after.

When the movie ended, the future rose between them.

“Would you come to London?” Archie asked quietly.

Brodie had been waiting for this. “Yes. If you ask me to.”

Archie’s eyes filled. “You’ll have to share me.”

Brodie pulled him closer. “I already do.”

“I’m in love with a Lego brick,” Josef said, grinning like it was the most normal thing in the world.

Tomas raised an eyebrow. “What do you know, Joe? Are you an AI prostitute now?”

“No,” Josef said seriously, as if clarifying a crucial fact. “I’m Gigolo Joe.” He slammed the cases into the trunk with mock solemnity.

“Are we ready?” Tomas asked.

“Ready when you are, brother. But make it fashion,” Josef said, voice smooth as a sales pitch.

Tomas laughed, a little bitter towards his little brother.“I used to be somebody. I used to take people places.”

Their parents groaned, caught between shame and exasperation. “Put some clothes on, Tomas!”

Jeffrey and his mafia. And me—only me—still unaware that I was God. A mutual understanding never consummated in public. We conspired like poets at war: Jeffrey with his loyal men, and I, followed only by those who believed in my every word. Yet I remember one moon-warmed night, when the sea breathed softly beneath us, and at the stern of a drifting ship, we clasped hands and swore our respect. The water glowed like milk around us. It was the start of a beautiful romance that put fear into the hearts of everyone except ourselves.

Harry Oldham is writing a novel based on his criminal and sordid past. To do so, he has returned to live at Park Hill, where he grew up, and the place that he once left behind. That was then and this is now, in which the old world collides with the new. (Parts 1 to 17 are available to read in the menu)

Perfectly Hard and Glamorous – Part 18

October 2025

There was a paperback of Saturday Night Fever published in 1977 by H. B. Gilmour. I read it when I was twelve. If I remember right, the novel said that Tony Manero looked like a young Al Pacino. In the film that came first, a girl he kissed on the dance floor gasped, “Ohh, I just kissed Al Pacino!”

I hadn’t a clue who Pacino was, only that he must’ve been something to look at. “Pacino! Attica! Attica! Attica!”

Decades later, Pacino published his autobiography at eighty-four. Everyone knows who he is now. It’s a decent book—above average—and I doubt he wrote it himself, but I’ll gladly be proved wrong. He writes beautifully about the part of life most people avoid thinking about: the last act, when the runway ahead is shorter than the one behind, as David Foster once put it.

Compared to Pacino, I’m still young. But sixty looms, and yes—I care a fuck. Quite a lot, actually.

I looked in the bathroom mirror and flinched. The face staring back didn’t belong to me. Wrinkles, dull skin, cheeks softening with age. Not the face of an eighteen-year-old; the face of an old man.

That night I dreamt of Andy, Jack, and me—partying by the Cholera Monument. Summer, though the skies were leaden. We were drunk, a boom box blaring New Musik. Rain began to fall, but we didn’t care. We danced, the drops sliding down our fresh, young faces. “It’s raining so hard now / Can’t seem to find a shore…”

We stripped to our boxers, soaked and clinging, leaping like fools. Paolo watched from under a tree, the outsider at the edge of a brotherhood. I wanted him to join us, but he stayed still, afraid.

When the song ended, our clothes were a sodden heap. We grinned, knowing this moment could never happen again. Paolo walked over, still fully dressed, and looked me up and down. Do you like what you see, Paolo?

He shook his head. When he finally spoke, I wished he hadn’t. “Harry, what are you doing? What happened to your body? Old men don’t behave like this.”

I woke to a shadow in the doorway. “Harry, you okay?”

Tom. He came and sat on the edge of the bed. “I think you were dreaming. You started shouting.”

“What did I say?”

“I don’t know, but you woke me up.”

“Fuck.”

“What were you dreaming about?”

I’d read that dreams fade fast because they live in the same part of the brain that controls movement—crowded out the moment we start to stir. But I remembered this one. And I blamed Al Pacino.

“What time is it?” I asked. “When did you get here?”

“Four a.m. After midnight, maybe. You didn’t hear me come in.”

“At least you haven’t lost your key yet. I take it you’ve finished your drug dealing for the night.”

He rolled his eyes. “Harry, I told you—what you don’t know won’t hurt you.”

Tom had mellowed since I met him two years ago. Back then he’d have clenched his fists and spat, “What the fuck’s it got to do with you?” Now twenty, he was as much a part of the flat as I was. He drifted in and out, sometimes gone for days, then suddenly asleep on the sofa when I woke.

Why I let him into my life, I’ve asked myself a hundred times. Just not tonight. Tonight, I was glad of him.

He lay back, staring at the ceiling. I went to piss. When I came back, he’d slid up beside me, hands behind his head.

“What are you doing?”

“I’ve never really been in your bedroom before.”

“Liar.” I’d made it clear it was off-limits, but I knew he’d snooped when I wasn’t around.

“Why did you become a writer?”

“Ah, the loneliest job in the world.” I hesitated, then answered.

“One night—a year before I left school—my parents came home from an open evening. Same story every year: teachers saying how useless I was. But that night, my mum came into my room looking excited. She said, ‘Mr Green, your English teacher, thinks you’ve got imagination if you put your mind to it. He said if you used better, longer words, you might pull through.’ My dad, standing behind her, added, ‘I told Mr Green he needs to speak properly first… but it’s a start.’ That was the only bit of hope they brought home.”

“Is that when you started writing?”

“Didn’t mean anything then. But in the early nineties, when I was broke, I had this client—older guy, fat—wanted me to piss on him. Easy money. We were lying on a wet plastic sheet in a hotel bed, talking. He worked for a publisher. Said I could make money writing about life as a London rent boy. I didn’t, of course—it sounded like work—but he told me to keep notes. Can you imagine?”

“And did you?”

“Not at first. Then one day I nicked a pack of exercise books from WH Smith and started jotting things down. Faces, nights, bits of talk. Eventually I began adding fiction, and that’s probably when I realised I could be a writer.”

My first book came out when I was in my forties. Nothing to do with rent boys. I’d drafted that novel, but no one wanted it—too sordid, too shallow, they said. One editor told me to try something else. So I wrote a formulaic thriller about a teacher investigating a missing student. I hated every minute of it, but it sold.

Tom turned toward me, and I braced for a jab. Instead, he said, “Maybe it’s time to revisit that old story. Nothing you write could shock anyone now. Might even fit with the book you’re working on.”

He hadn’t read any of my new work, not since that first night. My return to Sheffield and Park Hill had been interesting, if not productive. The book was two years late, my agent losing patience. Still—Tom had a point. I hadn’t thought about including the London years.

“There was a book published in the nineteenth century,” I said. “The Sins of the Cities of the Plain. No one knows who wrote it—some say a young rent boy named Jack Saul. It’s pretty explicit. I lived a life that echoed its pages once, long ago, when I was young… and now I’m not.”

Adonis was said to be the son of Theias, king of Syria, and his daughter Myrrha. There was nothing, it seemed, like a touch of incest to produce a child of exquisite beauty. When her father discovered her pregnancy, Myrrha fled and was transformed into a myrrh tree. Yet even in that form, she gave birth to a boy so lovely that Aphrodite herself took pity on him.

The goddess carried the infant to the underworld, entrusting him to Persephone’s care. But when Adonis grew into a youth of rare grace, both women fell hopelessly in love with him. It was inevitable, perhaps, that beauty would bring both adoration and ruin.

One day, while hunting, Adonis was fatally gored by a wild boar—sent, some say, by Artemis to punish his vanity. His blood mingled with Aphrodite’s tears and gave birth to the first anemone. Thus, his beauty became eternal, immortalised in a flower.

And so the story of Adonis was handed down through the ages, until it reached a boy called Banjo.

There is something wonderfully absurd about a boy named Banjo. The name had been chosen simply because his grandfather played the instrument—nothing more mystical than that. Had Banjo been plain, the name might have invited merciless teasing. But as fate would have it, he was beautiful—achingly so—and thus the name became a kind of charm.

He was the sort of young man who made strangers feel vaguely inadequate. They would take in his fine-boned features, his golden skin, his effortless grace, and feel the familiar pang of envy or desire. His beauty unsettled people, as though they were confronted by something not entirely human.

Banjo, however, found his looks exhausting. So he delighted in the single imperfection that spoiled the illusion: a missing front tooth. When people stared too long, he would flash a grin—a broad, dazzling smile—and there it was: the flaw that disrupted the marble perfection.

No one knew how he’d lost it. The rumours ranged from drugs to fights to some impoverished past before fame. The truth, however, was known only to Banjo, and he guarded it carefully. The missing tooth became his private rebellion against the myth others had built around him.

He liked the way it disarmed people, how it made him seem approachable, almost ordinary. It was a reminder that even gods have their fractures. Beauty, he thought, was not found in perfection, but in the quirks and vulnerabilities that betrayed our humanity.

If the ancient sculptors had carved him, they had stopped just short of finishing the smile—leaving him, deliberately, incomplete.

Banjo never replaced the tooth. He kept it as a secret charm, a flaw that told the truth: that myths do not survive in the real world, and perfection is the loneliest lie of all.

The café hums softly — a low murmur of spoons, voices, milk steaming behind the counter. I go there more often than I should, pretending it’s for the coffee, though I know that’s not true. He’s always there — Joseph — the boy with the rolled sleeves, the nice ass, the quiet smile. He moves with a kind of unthinking grace that makes the simplest gestures unbearable to watch. The tilt of his head, the tiny crease that appears between his brows when he concentrates. He hums under his breath when the machine hisses, wipes the same patch of counter top as if he’s polishing a secret into it. The light hits his hair just so, and I find myself timing my arrival to catch that moment when he leans over the counter and looks up.

Sometimes he catches my eye, and it feels like an accident — a spark that wasn’t meant to happen. He doesn’t know what he does to me: the curve of his wrist, the steam curling around his face, the way his voice seems to linger in the air a heartbeat too long. When his hand brushes mine as he gives me change, there’s the faint scent of roasted beans and skin, a small, electric pause before he turns away.

I tell myself I could stop if I wanted to. That it’s just a crush, just admiration. But I don’t want to. I want the ache. It isn’t love — not really — it’s too fleeting, too impossible. He doesn’t see me, not the way I see him. Yet there’s a strange tenderness in wanting without having, in sitting there each morning, pretending to read, tracing the rim of my cup as the warmth fades — while the boy behind the counter unknowingly becomes the centre of my day.

I collect fragments of him and carry them home like offerings. Sometimes I imagine saying his name aloud, but I never do. It feels too intimate, too final — as if it might break the spell.

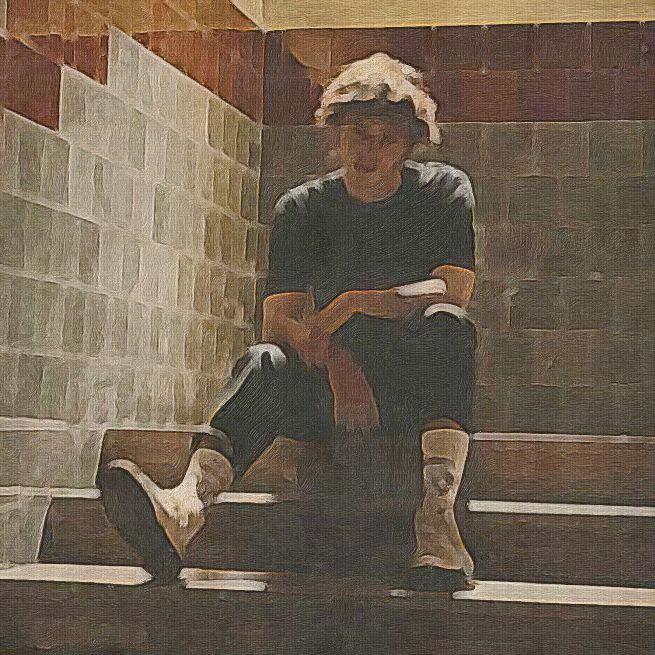

The night was still young as I sat quietly on the terrace, immersed in a book I had recently purchased from a second-hand bookstore back home. The book in question was an English translation of Oriana Fallaci’s work, originally titled Gli Antipatici and published in 1963. My edition bore the name Limelighters, and the author had thoughtfully explained that the Italian title did not lend itself to an easy English translation. According to Fallaci, “When Italians say antipatico, antipatici in the plural, they mean someone that they dislike on sight, and so if I was forced to choose a translation for antipatico, I would say unlikeable.” This explanation, rather than clarifying matters for me, added to my confusion, especially as I struggled to grasp Italian nuances.

The book is a collection of interviews with notable personalities; all recorded for the Rome newspaper L’Europeo using a portable tape-recorder. It begins with the line, “Many of the characters who figure in this book are my friends.” Fallaci proceeds to write friendly and insightful pieces about the stars of her era, including Bergman, Fellini, Hitchcock, and Connery. My bewilderment stemmed from the apparent contradiction between the book’s title and the content, which was anything but unlikeable in its tone and approach.

Most of the fifteen personalities featured in the book, along with Fallaci herself, have since passed away. The chapter that resonated most with me focused on El Cordobés, the Spanish matador and actor, who was still alive. Fallaci masterfully depicted his wild lifestyle: “he buys lined and squared exercise books, but then leaves them blank,” a habit I found relatable. She described him as being constantly surrounded by an eclectic group—banderilleros, priests, lawyers, in-laws, guitarists, boys from his cuadrilla, photographers, chauffeurs, Frenchmen intent on writing his biography, and a brunette whom he had just picked up in Granada. By tomorrow, he would have grown tired of her, and another would take her place. El Cordobés’s story captivated me; I imagined myself as one of the jealous boys from his cuadrilla.

At around seven o’clock, Cola called and mentioned that he was taking Cinzia to see a film, asking if I would like to join them. I declined, but he persisted, suggesting that my presence might encourage Cinzia’s younger brother to come along. “Bel ragazzo,” he confided with a wink.

Wearing an Inter football shirt, he showed little urgency in leaving and spent time browsing magazines before casually flicking through the international edition of the New York Times, which failed to capture his interest.

Cola never displayed any reservations about my homosexuality, even though I had kept this aspect of my life hidden from him when he was younger. I recall being invited to dinner by Signora Bruschi when Cola was about fifteen. After we had finished our Bistecca alla fiorentina, Cola rested his chin in his hands and, with the innocence of a choirboy, asked, “Is it true that you like to fuck boys?”

The curtains quiver, the window blows open and into the room flies a lovely boy clad only in cobwebs and autumn leaves and the juices that ooze out of trees.

The soul of a good time. But something changed. I’m not a social person anymore, but everybody wants me to be. They talk shit all night. I want to say, “Please go away, I prefer my own company now.”