Charlie didn’t go to Paris for Christmas. A family dispute—best addressed through absence—kept him away. Instead, he stayed with a cousin in Woodstock, near Blenheim Palace: an improbable place for pleasure. I was content with the opposite arrangement. Christmas alone. Eating, drinking, letting Netflix decide what mattered.

On Christmas Eve, I dreamed he climbed into bed and lay on top of me. His naked body was warm, yielding, unmistakably real. He kissed me. A faint musk rose from his skin—intimate, animal—stirring every sense at once. At last, I thought, this is the closeness.

I woke up with the sensation intact. The dream clung to me through Christmas morning, vivid enough to unsettle. I searched for an explanation and learned that smell can infiltrate dreams, especially when memory and desire are involved. Olfactory dreaming, they called it. Cologne was the usual example.

In the nineteenth century, a French physician, Alfred Maury, described inducing such dreams by getting his assistant to place eau de Cologne beneath his nose while he slept. On waking, Maury claimed to have dreamt of Cairo, of the perfumer Farina’s workshop, of adventures set loose by scent alone.

I hadn’t smelt Cologne. What lingered with me was the smell of a boy. And with it, a quieter truth: Charlie and I had never moved beyond kissing.

Someone, inevitably, had to puncture the theory. A psychiatrist dismissed the idea entirely. You don’t smell the coffee and wake up, she insisted. You wake up, then you smell the coffee.

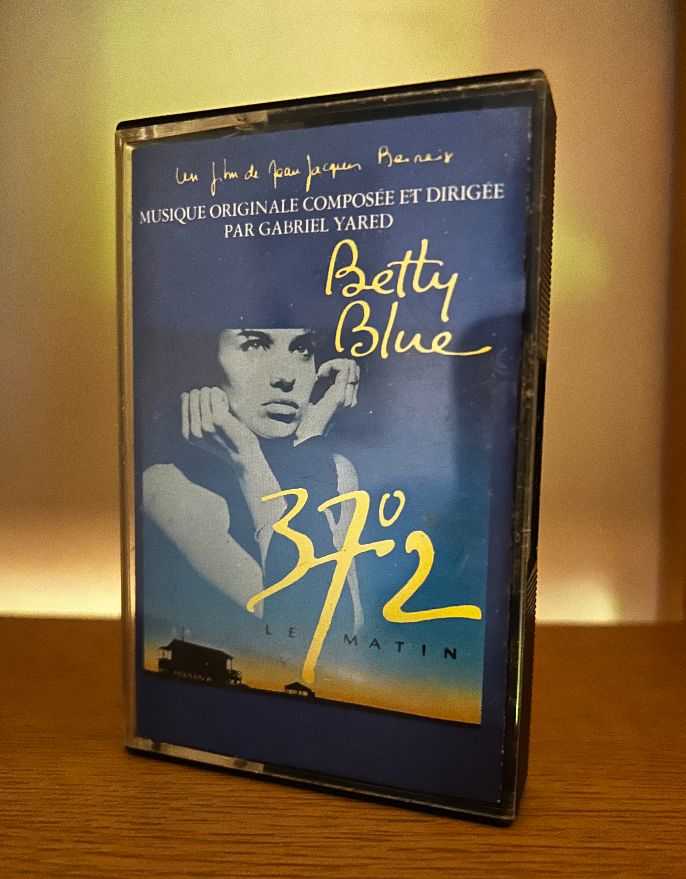

I abandoned science and let Spotify take over. It suggested an album by Wolfgang Tillmans, which surprised me. I’d known him only as a photographer. The music turned out to be a sound work made for an exhibition—joy and heartbreak threading through collapse and repair.

I first encountered Tillmans years earlier through a Pet Shop Boys video composed almost entirely of mice living on the London Underground. Ever since, I’d found myself scanning platforms, tunnels, tracks—without success. A memory surfaced: my friend Stephen once worked on a four-hour Tillmans sound installation of It’s a Sin. He now despises the song completely.

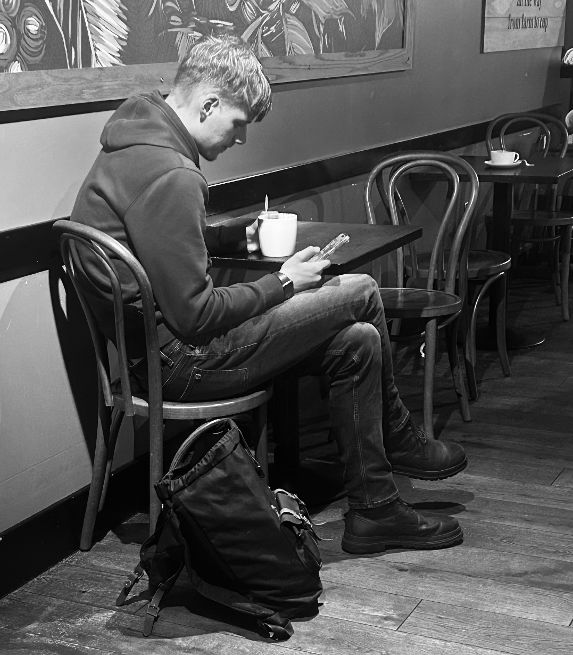

Christmas dinner was an indulgence of sorts: cold baked beans eaten straight from the tin. I spent an hour scrolling through films before accepting, once again, that choosing outlasts watching. I downloaded the Christopher Isherwood biography David had recommended—the one that never seems to end—and fell asleep within pages.

When I woke, the room had darkened. Charlie had messaged: Will be home tonight at about eight x.

Transport on Christmas Day was nonexistent, yet somehow he’d convinced his cousin to drive him 130 miles. When Charlie arrived, I asked where his cousin was.

“Gone back,” he said.

“You didn’t invite him in?”

“It’s Christmas. He’ll want to be home.”

“And petrol money?”

He hesitated. “I didn’t think of that.”

Our former lodger once called Charlie a “me, me, me person.” Another friend was less generous and called him an asshole. Perhaps it was cultural. Perhaps it was simply him. Charlie struggled to imagine himself from the outside. I told myself it wasn’t malice. Just a narrow field of vision.

Despite the journey, he looked fresh, handsome. He smiled; I mirrored it. I considered mentioning the dream, then decided against it.

“Why come back early?”

“I shouldn’t have left you alone,” he said, without pause. “It’s Christmas.”

While he dropped his bag in the bedroom, I switched on the tree lights. We exchanged gifts a day early.

His were faultlessly chosen: Salò on Blu-ray, Sargent, Ramón Novarro, Edmund White, a glossy Igor Mattio photography book. Then he disappeared into the studio and returned with a canvas. He turned it around.

It was me.

He’d painted me sitting, relaxed, looking beyond the frame—as if caught somewhere warmer, lighter. My eyes were generous. My mouth was kind. Around my neck he’d included a thin silver chain, a birthday gift I wore only on rare occasions. The detail felt deliberate, almost intimate.

“I painted while you were writing,” he said. “I hope you like it.”

I had never been seen like that before. Not by anyone. I felt exposed, and cherished.

“I don’t know what to say,” I told him.

“One day,” he said lightly, “when you’re old—célèbre—people will say, painted by his French lover.’”

Charlie went to shower. Alone, I recognised a flicker of shame. I’d suspected his absence was a ruse. I’d rehearsed disappointment, punished him silently for not being who I wanted. The dream—so tender, so convincing—had fed that instinct. Sex can exist without love; love can exist without sex. The phrase circled uselessly.

Still, it would be nice.

There it was again. That reflex. The mind’s preference for negativity over positivity.

Charlie returned wearing only grey jogging bottoms and a Santa hat. He stretched out beside me on the sofa, smelling faintly of crushed mandarins, and rested his head in my lap.

“A Christmas film,” he murmured. “Something cosy.”

I stroked his stomach as we watched The Holdovers: a misaligned teacher, a sharp-tongued cook, a boy full of grievance. By the end credits, Charlie was asleep.

I didn’t move. I was afraid that motion would undo everything. His weight, his warmth, the faint citrus on his skin—it felt provisional, like something borrowed. The room held its breath.

I loved him then with a sudden, almost painful tenderness. Not the urge to claim, but to preserve. To keep the moment intact, untouched by language or expectation.

I stayed exactly where I was.

And waited to see whether stillness could last.