Baron Corvo once told me in a dream that I should write something controversial. Terrible advice, obviously. But here we are.

I found a book in a charity shop that Charlie told me not to buy. He said it was distasteful. Which, of course, made me want it more.

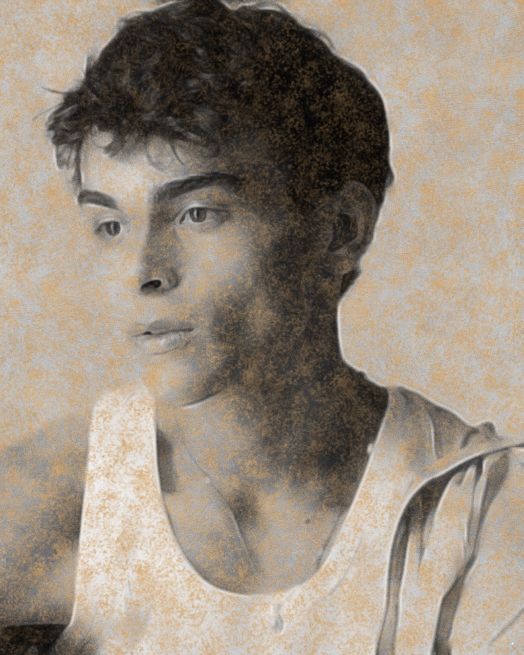

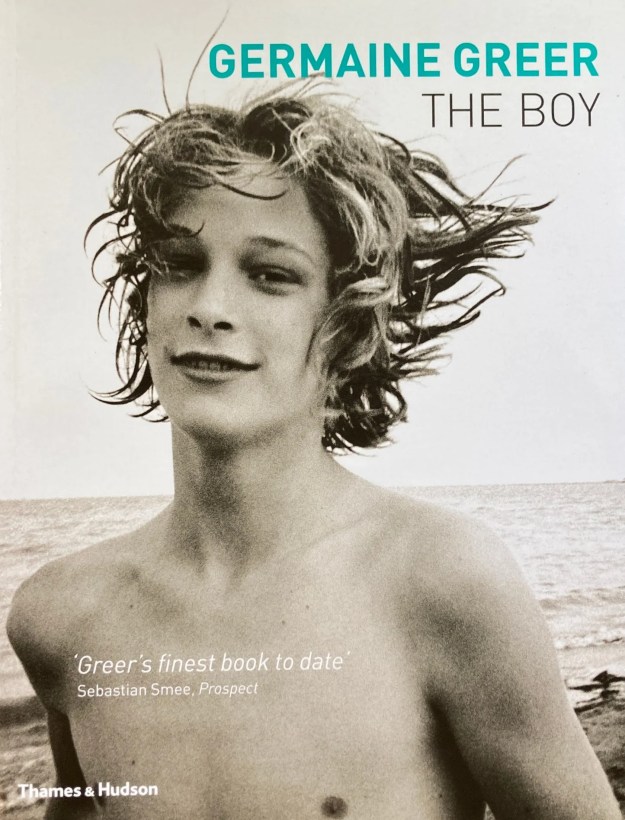

The book was Germaine Greer’s The Boy — a 2003 art history study about how young males have been represented in Western art. Greer argued that, for centuries, it was the male body — not the female — that dominated the gaze. Art, she said, used to worship men. Then we decided that kind of looking was shameful.

When it came out, The Boy caused an uproar. Greer said she wanted to help women reclaim their “capacity for visual pleasure,” to look at men the way art has long looked at women. Then she dropped her most infamous line: “A woman of taste is a pederast — boys rather than men.” Predictably, everyone lost their minds.

The book is filled with over 200 images — statues, paintings, portraits — each exploring what Greer called the “evanescent loveliness of boys.” The soldier. The martyr. The angel. The narcissist. The seducer. It’s the sort of book that doesn’t end up on display in Oxfam, which is precisely why I found it there.

The cover shows Björn Andrésen, the Swedish actor who played Tadzio in Death in Venice (1971). The photograph was by David Bailey, but Andrésen said no one asked permission to use it. He was furious — disgusted, even. “I have a feeling of being utilised that is close to distasteful,” he said. And the irony? The week I bought the book, he died, aged seventy.

Every obituary revisited the same scene: the audition tape from Death in Venice that was included in The Most Beautiful Boy in the World — a documentary about his life. Visconti tells him to smile. Then to undress. He laughs nervously. Strips to his trunks. Shifts under the gaze of men deciding whether he’s beautiful enough.

It’s hard to watch now. Visconti — Count of Lonate Pozzolo, titan of Italian cinema, and apparently, chaos in a cravat — ends up looking less like a mentor and more like a predator. But dead men can’t explain themselves.

When I was fifteen, I’d probably have thought that kind of attention was glamorous. Maybe I’d have handled it. Maybe it would’ve destroyed me. Hard to know. My own encounters with predatory men later on made Visconti look almost saintly by comparison. At least he left art behind. Maybe Andrésen’s story isn’t just one of exploitation, but what happens when fame and beauty collide with someone who’s too young to bear it.

Charlie, meanwhile, can’t stand The Boy. But he loves Death in Venice. He called Tadzio a “beau.” When I asked what that meant, he said: “The boy is beautiful. It’s sensuous, not pederastic. I’m surprised no one’s remade it.”

Which — yes — feels like a double standard. Both the book and the film are about the same thing: beauty. The kind we no longer know how to look at without flinching.

Could Death in Venice ever be remade?

I doubt it. The original is a masterpiece, and also completely unmakeable now. Mann’s 1912 novella was already controversial — a composer obsessed with a boy — and Visconti turned that tension into pure cinema. But in 2025, the moral landscape is different. Post-Me Too, post-Epstein, even looking can feel like a crime. No studio would touch it.

Unless you flipped it.

Make Tadzio older. Make the story less about sex and more about time — the hunger for youth, stillness, lost purity. Desire becomes existential, not erotic. If Visconti made the tragedy of seeing, a modern director — Luca Guadagnino, Todd Haynes, François Ozon, Joanna Hogg, Andrew Haigh — could make the tragedy of knowing you’re looking.

Visconti’s gaze was romantic. Ours would have to be self-conscious.

In their own way, both The Boy and Death in Venice celebrate the same thing — male beauty, youth, the brief perfection of being looked at before it fades. Once upon a time, that was sacred. Now it’s scandalous. Somewhere along the line, admiration turned into suspicion.

So yes, Baron Corvo told me to write something controversial. Bad idea from a worse man. But maybe he was right about one thing: sometimes, it’s worth writing about what we’re not supposed to look at.