I confess—I didn’t notice the rabbits at first. But there was something in the photograph that drew me in. It was taken by Izis Bidermanas, the Jewish-Lithuanian photographer, in Whitechapel, London, in 1951.

It’s quite possible that the boy in the image is still alive, but the rabbits, of course, are not.

Bidermanas worked primarily in France and is best remembered for his photographs of French circuses, Parisian streets, and commissions for the iconic Paris Match magazine. He befriended Jacques Prévert, the French poet and screenwriter; both were described as “urban wanderers.” A year after this photograph was taken, they published Charmes de Londres, a book of black-and-white photographs of post-war London by Bidermanas, accompanied by Prévert’s poetic texts—a vivid portrait of the “shabby old capital in its threadbare post-war years.”

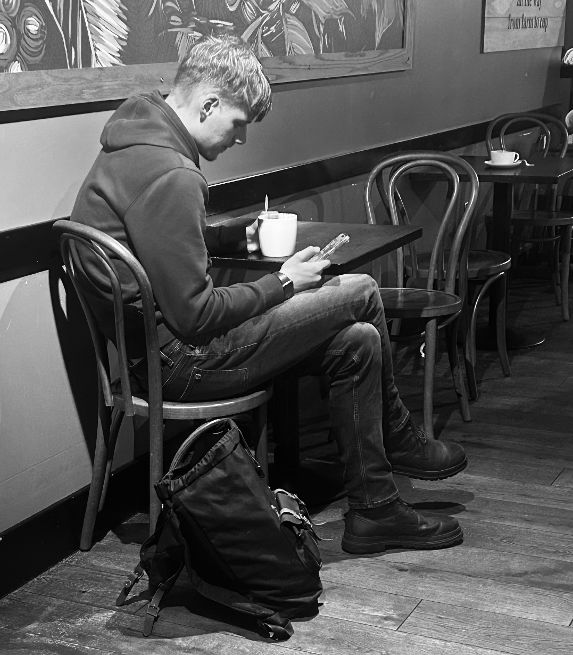

There is something both tender and prematurely adult about this image. A loosely tied scarf, a jacket slightly too big. His style seems effortless—almost cool—as if he had stepped out of his own decade and into ours.

He is someone out of sync with his time. The kind of boy you might spot today on the Underground platform, earbuds in, oversized coat slung over his shoulders. Certain types of youth are universal—postures, anxieties, and dreams that repeat across generations. It makes you want to know his story.

There is an angularity to his posture, an aloof tilt of the head. He strokes the rabbit but does not quite look at it. Tenderness in his hands, hardness in his shoulders. Quiet care, resilience, an emotional inheritance that compels him to protect something gentle, even if he has rarely known gentleness himself.

He seems too sharp, too perceptive for the smallness around him—working here because life left him no choice, waiting for the real story to begin. The rabbits were merely a way to earn a few coins.

What if he was drawn to things outside society’s expectations? Art, books, music—worlds not meant for boys like him. Perhaps he dreamed of Soho jazz clubs, photography, fashion—things his home would never have approved of.

He was a boy caught between worlds: childhood and adulthood, duty and desire, the past and the future. A timeless boy, carrying secret longings.