The summer ended and everything good about it disappeared too. Long days gave way to decline and by the time the leaves had turned the colour of brown leather, my world was unbearably melancholic.

Last night, I crawled through the undergrowth and scaled the stone wall like a hundred times before. Then I squatted under the horse chestnut tree from where I could see your bedroom. Third floor. Two windows from the left. There was no light, all darkness, and I knew that you’d gone.

“Remember the first day I saw you? When you stepped out of the sea and walked confidently towards where I lay on the sand. Beach blonde. Tanned. Swim shorts clinging tightly around your arse cheeks. The hairs on your body damp, glistening, and irresistible to a fourteen year old boy.”

I became a trophy, somebody to show off, to tease, and a plaything to practice on. I was the shadow that followed you, intoxicated when you were there, and bereft when you weren’t.

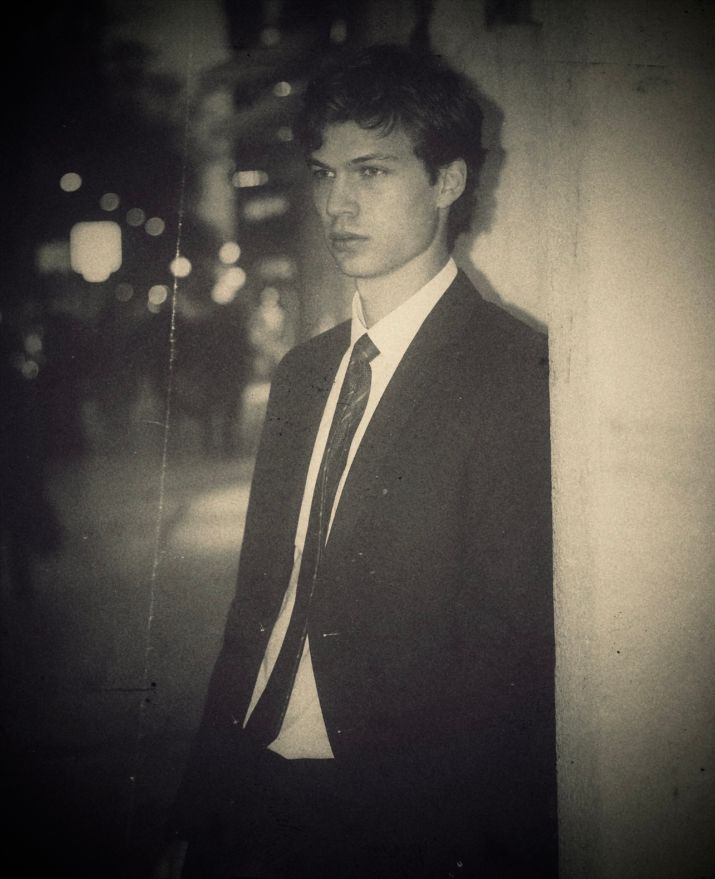

“They said you were called Theo, which seemed right for someone who came from a wealthy family and lived in a big house with iron gates and a long drive. Theo who liked to surf, chat with girls, and listen to indie music until the sun came up.”

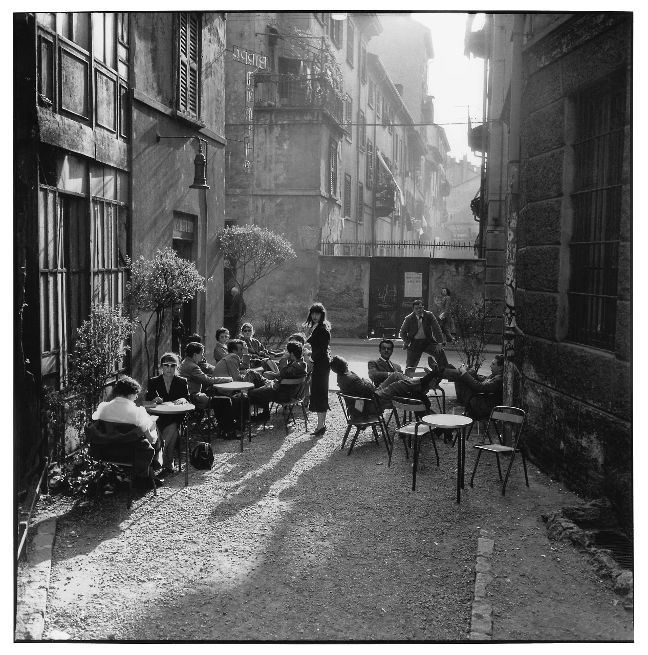

Your friends tolerated me because I belonged to you and were obliged to include me in everything. Those days in the sun, laying on the beach, and going into town when you looked out for me and made sure that I didn’t go without. Sometimes we did nothing at all. But the days I enjoyed most were the ones when there were only the two of us. When you put your arm around my shoulders and treated me like an adult.

“Remember when I snapped my surfboard? It hit the rocks and drifted out to sea, and I nearly cried because all I could think about was not being able to ride the waves anymore. The next day you bought me a bright yellow Thunderbolt Slasher board that cost you well over a grand.”

I didn’t want to share you with anyone, but I could never say that, and when you ended up with a girl, I’d scramble through the undergrowth and wait with the foxes and rabbits until you came home. And I would look with envious eyes as you undressed and strutted naked around the room that was bigger than our cottage by the harbour.

“Theo likes you, they said. He loves you like a little brother. The kind who throws you over his salty shoulders and squeezes until you become aroused. Except that I didn’t want to be a little brother, I wanted to be a lover. A girl called Olivia, who smelled of Unicorn farts, said that I was far too young.”

The last thing you did before going to bed was shower, and with damp hair and a big fluffy towel around your waist, you’d open the window and survey the land that one day would be yours. Then the light would go out, and I’d wander around that massive garden. I would strip naked and swim lengths of the pool that you said you pissed in when you were drunk. Then, I’d imagine climbing the ivy and slipping into your bedroom.

You asked me about the scratches on my arms and legs. When I blushed and said that I’d got them playing football, you’d winked and said that it looked like I’d been fighting with brambles. That was the moment when I realised that you’d known all along, and despite my best efforts at concealment, you’d seen me in the shadows. But then I knew that those nightly performances had been for my benefit.

“I hated the girls who talked with you and hated the boys even more. They were enthralled that you rode a fast Ducati down narrow country lanes, that you could play Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto, and would be going to Trinity College.”

The room is sulking in your absence. Memories won’t last forever. When I sat under the tree last night, I watched your parents coming and going in their flash cars. Were they thinking about you? Were they worrying? They didn’t seem to care. But I knew that you’d be charming the posh boys and girls of Cambridge, and I fretted about whose boxer shorts or knickers might come off first.

“Theo is going away, they said. He must prepare for a life worthy of his ancestors. The last thing you did was to give me a peck on the cheek, a scent of Aqua di Gio, and a trace of pepperoni pizza on your breath.”