Harry Oldham is writing a novel based on his criminal and sordid past. To do so, he has returned to live at Park Hill, where he grew up, and the place that he once left behind. That was then and this is now, in which the old world collides with the new. (Parts 1 to 17 are available to read in the menu)

Perfectly Hard and Glamorous – Part 18

October 2025

There was a paperback of Saturday Night Fever published in 1977 by H. B. Gilmour. I read it when I was twelve. If I remember right, the novel said that Tony Manero looked like a young Al Pacino. In the film that came first, a girl he kissed on the dance floor gasped, “Ohh, I just kissed Al Pacino!”

I hadn’t a clue who Pacino was, only that he must’ve been something to look at. “Pacino! Attica! Attica! Attica!”

Decades later, Pacino published his autobiography at eighty-four. Everyone knows who he is now. It’s a decent book—above average—and I doubt he wrote it himself, but I’ll gladly be proved wrong. He writes beautifully about the part of life most people avoid thinking about: the last act, when the runway ahead is shorter than the one behind, as David Foster once put it.

Compared to Pacino, I’m still young. But sixty looms, and yes—I care a fuck. Quite a lot, actually.

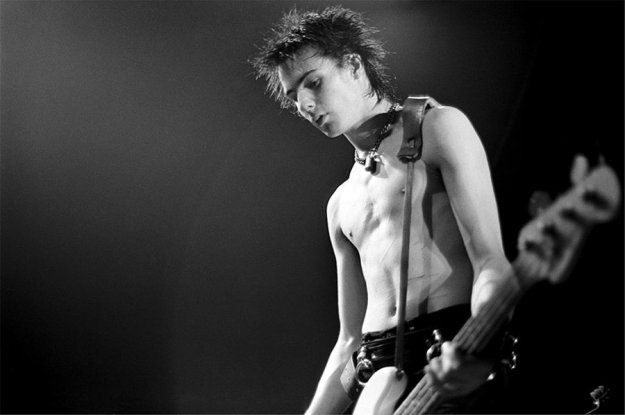

I looked in the bathroom mirror and flinched. The face staring back didn’t belong to me. Wrinkles, dull skin, cheeks softening with age. Not the face of an eighteen-year-old; the face of an old man.

That night I dreamt of Andy, Jack, and me—partying by the Cholera Monument. Summer, though the skies were leaden. We were drunk, a boom box blaring New Musik. Rain began to fall, but we didn’t care. We danced, the drops sliding down our fresh, young faces. “It’s raining so hard now / Can’t seem to find a shore…”

We stripped to our boxers, soaked and clinging, leaping like fools. Paolo watched from under a tree, the outsider at the edge of a brotherhood. I wanted him to join us, but he stayed still, afraid.

When the song ended, our clothes were a sodden heap. We grinned, knowing this moment could never happen again. Paolo walked over, still fully dressed, and looked me up and down. Do you like what you see, Paolo?

He shook his head. When he finally spoke, I wished he hadn’t. “Harry, what are you doing? What happened to your body? Old men don’t behave like this.”

I woke to a shadow in the doorway. “Harry, you okay?”

Tom. He came and sat on the edge of the bed. “I think you were dreaming. You started shouting.”

“What did I say?”

“I don’t know, but you woke me up.”

“Fuck.”

“What were you dreaming about?”

I’d read that dreams fade fast because they live in the same part of the brain that controls movement—crowded out the moment we start to stir. But I remembered this one. And I blamed Al Pacino.

“What time is it?” I asked. “When did you get here?”

“Four a.m. After midnight, maybe. You didn’t hear me come in.”

“At least you haven’t lost your key yet. I take it you’ve finished your drug dealing for the night.”

He rolled his eyes. “Harry, I told you—what you don’t know won’t hurt you.”

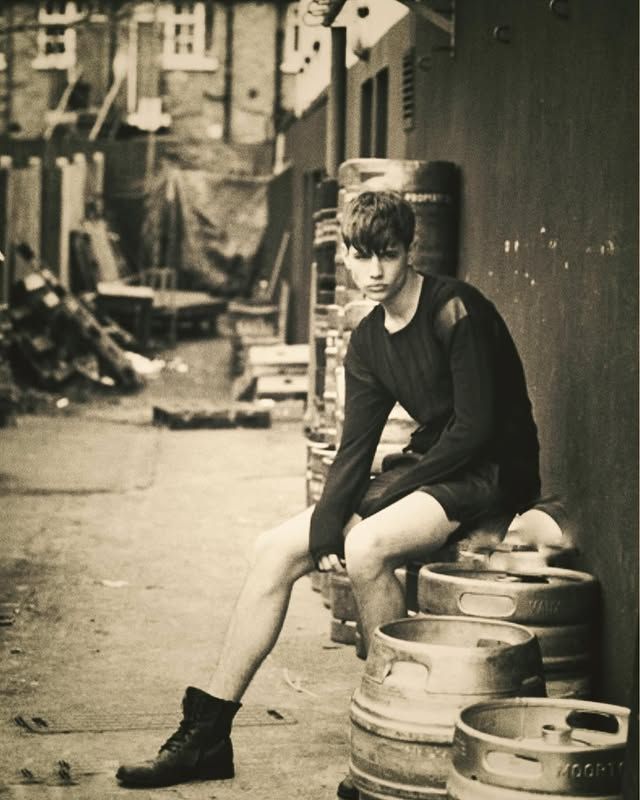

Tom had mellowed since I met him two years ago. Back then he’d have clenched his fists and spat, “What the fuck’s it got to do with you?” Now twenty, he was as much a part of the flat as I was. He drifted in and out, sometimes gone for days, then suddenly asleep on the sofa when I woke.

Why I let him into my life, I’ve asked myself a hundred times. Just not tonight. Tonight, I was glad of him.

He lay back, staring at the ceiling. I went to piss. When I came back, he’d slid up beside me, hands behind his head.

“What are you doing?”

“I’ve never really been in your bedroom before.”

“Liar.” I’d made it clear it was off-limits, but I knew he’d snooped when I wasn’t around.

“Why did you become a writer?”

“Ah, the loneliest job in the world.” I hesitated, then answered.

“One night—a year before I left school—my parents came home from an open evening. Same story every year: teachers saying how useless I was. But that night, my mum came into my room looking excited. She said, ‘Mr Green, your English teacher, thinks you’ve got imagination if you put your mind to it. He said if you used better, longer words, you might pull through.’ My dad, standing behind her, added, ‘I told Mr Green he needs to speak properly first… but it’s a start.’ That was the only bit of hope they brought home.”

“Is that when you started writing?”

“Didn’t mean anything then. But in the early nineties, when I was broke, I had this client—older guy, fat—wanted me to piss on him. Easy money. We were lying on a wet plastic sheet in a hotel bed, talking. He worked for a publisher. Said I could make money writing about life as a London rent boy. I didn’t, of course—it sounded like work—but he told me to keep notes. Can you imagine?”

“And did you?”

“Not at first. Then one day I nicked a pack of exercise books from WH Smith and started jotting things down. Faces, nights, bits of talk. Eventually I began adding fiction, and that’s probably when I realised I could be a writer.”

My first book came out when I was in my forties. Nothing to do with rent boys. I’d drafted that novel, but no one wanted it—too sordid, too shallow, they said. One editor told me to try something else. So I wrote a formulaic thriller about a teacher investigating a missing student. I hated every minute of it, but it sold.

Tom turned toward me, and I braced for a jab. Instead, he said, “Maybe it’s time to revisit that old story. Nothing you write could shock anyone now. Might even fit with the book you’re working on.”

He hadn’t read any of my new work, not since that first night. My return to Sheffield and Park Hill had been interesting, if not productive. The book was two years late, my agent losing patience. Still—Tom had a point. I hadn’t thought about including the London years.

“There was a book published in the nineteenth century,” I said. “The Sins of the Cities of the Plain. No one knows who wrote it—some say a young rent boy named Jack Saul. It’s pretty explicit. I lived a life that echoed its pages once, long ago, when I was young… and now I’m not.”