Charlie told me a story. He said that he woke up this morning and found that I was missing. When I didn’t reappear after a couple of hours, Charlie went to the neighbour and knocked on her door. “Have you seen Miles?” “No, I haven’t,” she replied. Charlie went to the other neighbour and knocked on the door. “Have you seen Miles?” “No, I’ve not seen him,” he answered. Charlie left the apartment and walked to the block on the other side of the road. He climbed three flights of stairs and knocked on Mrs Hayward’s door. “Have you seen Miles?” But she slammed the door in his face.

Charlie told the story with such conviction that you almost believed him. But it is a way of saying, “You went out and didn’t tell me where you were going.” At times, he tries to be funny and makes the point with dramatic effect. Other times he can be blunt, like French boys sometimes are.

“Your mobile rang, and the call was from someone called Ben. Who is Ben? How do you know him? Why is he ringing you? Have you slept with him?” I’ll point out that Ben is the landlord of the apartment. “I see,” he would say, “But do you like him?”

For these reasons, I don’t tell Charlie everything, and that can sometimes cause problems. Thomas, his brother, told me that Charlie was insecure, and is frightened that he might lose everything.

I don’t like people reading what I’ve written, which is why most of my work is published under a pen name. Charlie will look over my shoulder and try to read what is on the screen. I will immediately close the laptop, and this infuriates him. “Why will you not let me read it? Is it because you are writing about me?” “It’s not about you,” I’ll tell him, “It is a short story.”

I never show him because he’s right. I often write about him, and if the story wasn’t about him, he would see something to convince himself that it was.

I suppose it’s my secret, rather like Charlie’s mysterious trips to Europe, of which I still know nothing, and now he’s declared that he’s off to Lille again. I’m not invited and in response I’ve decided to go to Italy in November. When I tell Charlie, he assumes that he’s going with me.

I will enjoy the few days of freedom while he’s away and have already made plans to go out with Levi, the Polish boy with the broad Yorkshire accent, who asked a serious question. “Does that mean that you’ll be wanting to sleep with me?” The prospect is exciting. “If I asked, would you say no again?” Levi smirked. It struck me that although he wanted to move in with his girlfriend, there were few signs of him doing so. “Like I said before, we shall have to see,” he replied, “But remember that you have a boyfriend.” He hadn’t said no, and I took that to mean that there was a possibility, and I started counting the days.

But Charlie doesn’t miss a trick. “Please make sure that you behave while I’m away, because when you’ve had a drink, you have mischief in you. While the cat’s away, the mice will play.” He repeated this to Levi who told him that if he was so jealous then he should consider staying home.

It is a brie, tomato and salad sandwich. I swear that the one I’m obsessed with has added part of himself to it. That extra ingredient makes it the best sandwich I’ve ever tasted.

Harry Oldham is writing a novel based on his criminal and sordid past. To do so, he has returned to live at Park Hill, where he grew up, and the place that he once left behind. That was then and this is now, in which the old world collides with the new. (Parts 1 to 16 are available to read in the menu)

Part 17

September 1983

The room is dark, and men are lurking in every corner. A spotlight clicks on, and we are blinded by light. The focus is on us, naked and vulnerable, and those hungry eyes that think we are the most beautiful boys in the world. Music starts. David Grant’s ‘Watching You, Watching Me.’ The track has become our signature tune, and we know when to start dancing together. Our bodies touch and we feel every part of each other. Swirling, swaying, dipping, gliding, grinding, twisting. “I’ve been watching you, watching me. I’ve been liking your baby liking me.” The men know that this is the appetiser. Soon, floppy boys will become hard boys and do unthinkable things to one another. I look at Paolo, and for the first time I see that he is enjoying it. He sticks his tongue inside my mouth, and I know that it isn’t an act anymore. “I’ve been watching you, watching me. I’ve been liking your baby liking me.” I imagine Andy and Jack are sitting with the men, disgusted with us… no, only me… and when I get outside, they will beat the shit out of me. “But I’ll tell them, “I earn fifty quid, and men adore me, and I get to do it with someone who loves me.”

*****

There was a moment last night when everything seemed… well, perfectly hard and glamorous. It was when things were going so well that you didn’t expect it to come crashing down. But that’s exactly what happened. The music was so loud that I hadn’t heard the splintering wood. I hadn’t noticed the shadows who spilled into the room. And I was drunk enough not to realise that there was danger. The music cut and there were shouts of protest. Paolo froze. Then the lights came on to reveal the chaos. The men who lurked in corners were handcuffed and dragged out by police officers. Amidst all this, we were naked. I grabbed Paolo and quickly pulled him through another door. “I thought you’d both exit stage left,” said Frank Smith who stood in the next room. He threw a couple of blankets at us. “Cover yourselves up sluts, there’s a car waiting outside.”

*****

My first thought in the back of that unmarked Ford Escort was the money that I would lose. Two hundred quid a month on top of my dole money meant that I was never without. Nobody questioned my newfound wealth. New clothes, beer money, and cash to spare. Then I worried about the hellish time that lay ahead. The copper in front didn’t say anything. We drove along Ecclesall Road and took a turn into a side street, where he parked outside the one house that still had a downstairs light on. He opened the door and gestured for us to follow. The door opened and a dumpy woman looked on in amusement as we walked barefoot into the hallway. The copper disappeared and she closed the door. “Go through to the kitchen lads.” She wouldn’t have looked out of place on Park Hill, but spoke kindly, and her house was nicely decorated. We sat at the table with only blankets covering our modesty. “Do you want anything to eat? A cup of tea?” We shook our heads. “Well, I suggest you both take a shower, and I’ll show you where you can sleep. I’ll fix you some clothes for the morning.” This was the first time that we met June, but it wouldn’t be the last.

******

“At least you were spared the disgusting final act.” Neither of us had slept and were grateful when June brought us mugs of hot tea in the morning. She’d prepared a fry up, and now sat listening as Frank Smith paced up and down with a cigarette. “I told you to be patient, but with the names you gave us, and the fact that we had a spy in the camp, we’ve got enough to take these buggers down.” I was tired and jittery. “What’s going to happen to us?” “Nothing. I need you for the next part of the plan. I told you that we’re pitching bad guys against each other, and as far as the others are concerned, we’ve busted their rivals. The thing is, they think that they’ve got coppers on their side… but that’s not how it’s going to play out. They’ll be keen to get hold of you, and I’m not exactly going to stand in their way.” Paolo looked worried. “Will we have to go to court?” “Nah, that would ruin everything. I’ve got ways of keeping you out of it. I need you to go home as if nothing happened and wait for them to get in touch. When they do, play hard ball, demand more money because you’ve got a reputation now.” Frank laughed. “I think you’ve enjoyed yourselves, so why not make good money at the same time. And Harry, one good turn deserves another. We’re dropping the robbery charges against your mates. I didn’t trust that cow in the shop anyway, she’s got a record longer than your arm, and I’ve told Billy Mason that if anything happens to any of you, I’ll be coming down on him. The trouble is, I can’t trust him.”

When we left June’s house, she gave us both a peck on the cheek. “Take care boys. Frank can be a bastard, but he’s got your best interests at heart.” I wasn’t convinced. “It’s going to mean promotion for him, and then he’ll fuck us off.” She smiled. “I’ve known him a long time, and he’s brought a lot of kids through this door. He’s explained everything. You’re both very brave and I know what you’re doing seems wrong but think of all the kids that you’ll be saving in the future.” Paolo whispered in her ear. “I’m scared.” She patted his curly hair. “Don’t be afraid to come around anytime you want.”

A message from Thomas in Paris. “When am I going to see you?” What a predicament? I’d like to see him again, but there is the problem of Charlie, the guy I sleep beside every night. “Hey Charlie, I’m off to Paris, and if I’m lucky, I’ll be able to get my end away with your brother, but hey, it’s more than I get from you.” I’m excited and tempted to go, but I’m afraid of the repercussions.

I love Charlie, and I think he loves me, but the one thing I want more than anything is to make love to him. But he is a strange breed, and sex is as far away as the day I met him.

The other day I was tapping into my phone, and he came up behind me. “What are you writing?” “I’m making notes,” I replied. I saw that look in his eyes. Charlie thinks that mobile phones are for messaging and taking photos. He eyed me with suspicion. “”Who are you messaging?” “Nobody. I’m writing an article for someone.” It sounded as convincing as I wanted it to be. The truth was that I was writing what you are reading now, and he didn’t believe me.

A few nights ago I tried to cuddle him in bed. “No,” he said, “I am very tired.” He put EarPods in and listened to music. That was the biggest fuck off ever. I turned over and decided that I wouldn’t be humiliated again. “If I can’t get it from you, I’ll get it somewhere else,” I murmured, knowing full well that Charlie wouldn’t hear me, but at least I’d said it.

I’ve looked at past sexual conquests and realise that the hardest part was always getting that person home and into bed. With Charlie, the challenging part was easy, but the next stage is even more difficult. The person you desire most is within reach, inches away, and yet you are forbidden to touch.

I compare it to the euphoria of reaching the gates of heaven, and then being turned away because you’re not supposed to be there. Beyond those pearly gates you can see sunshine, utopia, and eternity, but you’re sent to hell instead.

It’s not that Charlie isn’t affectionate. He might give me a peck on the cheek and make me feel like I’m walking on air. But that’s as far as it goes. Imagine how that feels? The person that everybody thinks is your partner, and doesn’t want to make love to you.

I made the mistake of mentioning this to a friend, and he came up with a thousand and one shit reasons why this might be – life distractions, stress, emotional tension, low desire, physical, and mental health issues, sexual pain, and even brought up erectile dysfunction. That last one definitely wasn’t true because I’d seen Charlie walking about the apartment in his underpants with a definite hard-on . “Talk to him about it,” he said. I told him that I didn’t even know if Charlie was officially my boyfriend. “No,” I replied, “It’s much easier to sleep with someone else instead.”

I feel that Thomas is too good a chance to miss. I want him, I need him, and have reason to believe that he wants me, but then I remember Charlie’s temper tantrums after his brother visited.

When Levi came home last night, he sat opposite in just a pair of football shorts, and, at that moment, he was the most beautiful boy in the room. I remembered the drunken conversation we’d had a few months ago when I’d told him that I wanted to get him into bed. He’d graciously turned me down. This time I wasn’t drunk and wanted to say it again. But I didn’t, because a voice inside my head was saying, “At this time, anybody with a penis looks attractive to you.” Sadly, that voice was right.

The apartment is a confusing place these days. Being in his early twenties, I would expect Charlie to like Chase and Status, Stormzy, Billie Eilish, Charli xcx, or Taylor Swift because everyone insists that we MUST like her. It’s not that Charlie doesn’t like them, but he says that they are “too generic.” The French boy wants to be different and has declared his love for opera.

Charlie goes to operas on his own and comes back gushing. “It is the sound of the vocalists,” he says. “They have the ability to tell a story, evoke emotion, and provide sensory overload.”

I’ve never understood the appeal of opera and remain convinced that it is a cultural art form for the elderly. Charlie tells me about the people he meets, and I decide that they must be old because young people don’t go to the opera. “I like being the youngest person in the audience and command respect.”

He told me a story about a wealthy Latvian woman who dressed in expensive furs and went to the opera on her own because it was something she did with her late husband. “Tears filled her eyes, and she insisted that I hold her hand throughout the performance.” I didn’t tell him that she was hoping for a shag.

I told Charlie that I once went to see ‘La traviata’ and because it was in Italian, I didn’t understand it, found it incredibly boring, and had stayed clear of opera since.

“That is a classic opera,” Charlie cried. “‘The fallen woman’ by Giuseppe Verdi, but did you know that it was based on a French novel, La Dame aux Camélias, by Alexandre Dumas fils. Strangely enough, I didn’t. “However, French operas are much better than Italian ones.”

I challenged him to name French operas and expected him to flounder. “There are many,” he replied, “and the list of composers is impressive – Rameau, Berlioz, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet, Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc, and Messiaen.”

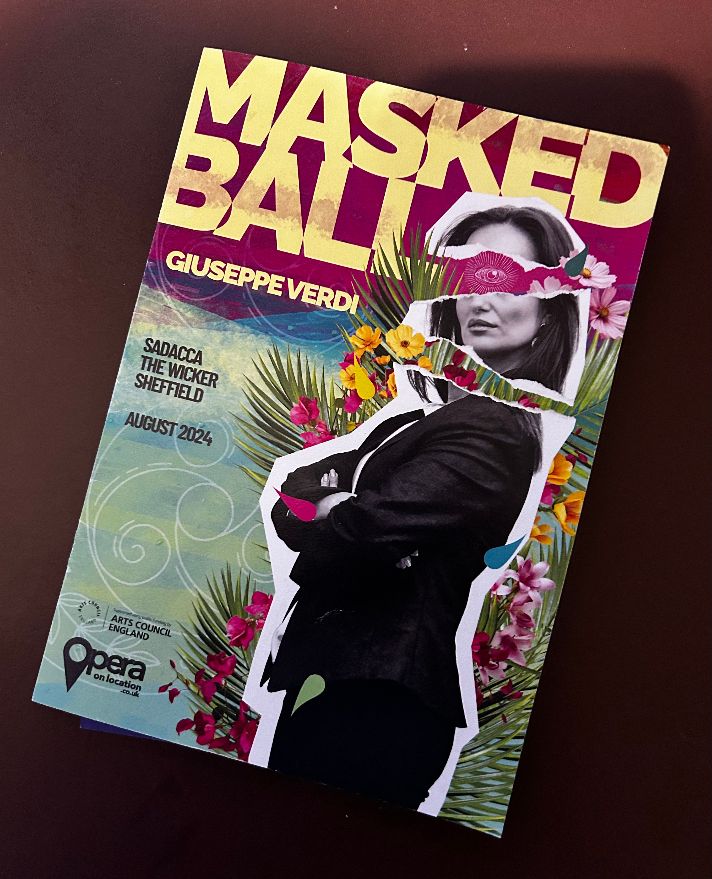

Last week, Charlie invited me to go to the opera with him, and after enduring days of pestering, I agreed. “Ot is Un ballo in maschera,” he said, “’A Masked Ball’ for the ignorant English, and it is also by Giuseppe Verdi, but this will be sung in your own language.”

The opera was taking place in an old factory unit, and I couldn’t understand why Charlie had dressed in a dark suit and white shirt, and then spent ages styling his thick black hair. “It pays to look smart. I want you to take photos of me while we are there, and I can post the best of them on Instagram.” I wanted to say, “But I thought the best photos involved you being naked.” But I daren’t say it, because, if you remember, I’m not supposed to see Charlie’s Insta account.

Charlie insisted on buying glasses of wine beforehand and was disturbed to find them served in disposable cups. We were seated on the front row, and I couldn’t resist saying that I’d never seen so many walking sticks. At this, he punched me hard on the thigh which I found quite exciting. I browsed through the programme and read the synopsis so that I had a chance of understanding what was about to happen.

The opera wasn’t what I expected. The singing was incredibly powerful, and I understood every word, realising that it had been adapted for modern times. I had to admit that I liked it enormously. Charlie frowned when I told him this, and he confessed that although he too had found it entertaining, he’d struggled to follow the story.

Back at the apartment, we told Levi about our night at the opera, and he looked at us as though we were both mad. “What have you been up to?” Charlie asked him. The Polish boy with the broad Yorkshire accent looked pleased with himself. “I watched Emmerdale, Coronation Street and then spent ages browsing Pornhub!”

Harry Oldham is writing a novel based on his criminal and sordid past. To do so, he has returned to live at Park Hill, where he grew up, and the place that he once left behind. That was then and this is now, in which the old world collides with the new. (Parts 1 to 15 are available to read in the menu)

Part 16

August 2023

Back in the nineties, I was living in a seedy Camden bedsit because that was all I could afford, and its shabby appearance reminded me of home. It hadn’t always been like that. For a decade, I’d earned good money, gratifying rich London blokes who considered a slim northern lad exotic. The thicker I came across, the dirtier I acted, the more cuts and bruises I showed, the more beatings I accepted, the more money I earned.

I knew that nothing lasted forever, and as I slipped into the second half of my twenties, I realised that I’d passed my prime. The older guys didn’t want me anymore, and I became one of many who hung around King’s Cross earning nothing.

I moved into that bedsit because it was owned by a market trader who promised to charge a nominal rent in exchange for sex. When someone younger came along, his attention turned, the rent went up, and I was desperate.

I barely managed to survive, and decided to let a dodgy mate sleep on the sofa because he had no place to go and stole food for the both of us. One day he disappeared, and so did most of my possessions.

Why did I think about this today?

Tom is asleep on the sofa, his clothes strewn across the floor. and for the first time I notice two mobile phones. One of them lit up and a message appeared on the screen. “Call me bro’.”

For the past two months, Tom had turned up two or three times a week. He’d call around midnight, and ask to stay, and I always let him, even though I suspected that he was mixed up with a bad crowd. Who am I to judge? We’d talk and then he’d fall asleep, and I’d put a blanket over him.

In the morning, I’d watch him from the table where I worked. I always wrote better when he was around. At lunchtime he’d wake up, stretch, stick his hands down the front of his underpants and stare at the ceiling.

Today he caught me looking at him. “What?” he asked.

“I’m asking myself why you want to sleep on my sofa. I’m also wondering why you need two mobile phones.”

“I’ll go then”

“I’m not telling you to go.”

“I like it here. I’m not causing you any trouble.”

“That’s for me to find out.”

Tom got up and wandered to the kitchen area. Kettle on. Teabag in a mug. A bowl of bran flakes. I saw that he was wearing brand new Calvin Kleins.

“Are you eyeing me up?”

I laughed and realised that I was doing exactly that. “I forgot what an arsehole you are when you wake up.”

He attacked the cereal and sulked like a petulant child. When the bowl was empty, he put the spoon down and stared at me. “Why do you let me stay here?”

“Maybe it’s because you remind me of myself when I was your age. But that would mean that you were in trouble.”

Tom opened a jar of peanut butter, stuck his finger inside, and licked the contents off it. Then he helped himself to the pack of Marlboro Gold on the table. “I can look after myself.”

This was the problem.

In the short time that I’d known Tom I had come across the barrier that he’d built around himself. I tried to break through it, but he was tough.

Being as he was, he perhaps thought it was the best thing to do. He was unwilling to listen, not ready to compromise, super competitive, and often frustrated. I thought that he was struggling beneath the surface, and sometimes I believed that he was trying to get a rise out of me.

It was as if Tom was grappling with control over something – rejection, pain, or loss – or was it something deeper, like love, or a relationship? Getting close to someone might hurt him. Maybe he was issuing a challenge. Did I care enough to break that barrier down?

I wanted to tell him that I could be that person who might draw him out but was aware that I was only doing it for my own gratification.

Tom sat, half naked and beautiful in the morning sun, and I saw myself all those years ago. This was how Paolo might have seen me then, with hidden sentiments, secrets, dreams, sorrows, trouble, and pain.

“I can help you if you want me to.”

Tom sat back in the chair and flicked cigarette ash into the empty mug. “If I accepted your help, that would ruin everything.”

“We have too many books,” I told Charlie. It was true, the apartment was being taken over by books that had been bought at second-hand bookshops and charity stores. They filled the shelves and were now stacked in corners. ”It’s time to get rid of some of them.”

He looked at me with disgust. “They are collectible,” he cried. “These books will increase in value.”

We had a routine, like an old married couple. We would go to affluent parts of the city looking for rare books that people had no use for anymore. Intellectuals lived here, and there was a chance that we might stumble upon old art and photography books. “You will not find a Katie Price autobiography in these shops,” Charlie explained. “These places are full of lost treasures. Remember that book you bought for ten pounds and is now worth a fortune?”

Charlie was referring to Germaine Greer’s The Boy that we’d later seen in an antiquarian bookshop for one hundred pounds. “A very controversial book,” he’d said. “It is almost paedophilic.” Except that Charlie’s French had difficulty translating it and made me smile, and this allowed him to think that I was confirming his opinion.

I secretly admit to enjoying these days out, and then retiring to a favourite cafe – the one that sold fish finger filled croissants – and examining what we’d bought. Charlie would carefully display the books on a table alongside cups of coffee with flowery patterns in the froth and take a photo that he posted on Instagram.

“I think that you have become a bibliomaniac,” I told him.

“That word sounds French,” he replied, “but I do not understand it.”

It means that you are an addict, and one day the floor of our apartment will collapse under the weight of the books.”

There was another point I wanted to make, but chose not to, because it would end in an argument. Charlie had a habit of starting novels and never finishing them, and I repeatedly found bookmarks after thirty pages or so. He denied this, but I had yet to see him read a book from beginning to end.

Charlie believed I had more books than him. This might have been true once, but I had learned to thin them out. I’d started putting them in the recycling, because it was a quick fix, but this always felt unacceptable. And then I chose charity shops to dispose of them, the same ones that we visited now. The drawback was that my friends shopped in them as well, and often gave the same books back to me. But no, I’d decided, Charlie had more books than me.

“We need to categorise the books,” Charlie explained, as if this was a compromise. “We can put art books together, likewise photography books, and so on. Then our visitors will realise how sophisticated we are.”

“There might be a short term solution,” I joked. “Levi is moving out soon, and we could turn his bedroom into a library.”

Charlie looked doubtful. “I had thought that we might rent the room out again.”

“I didn’t think that you liked anybody else living here, and I remember the fuss that you made when Levi moved in.”

“That was different,” he replied, “I didn’t know him, but now I will miss him when he is gone. And besides, the extra money is useful.”

This was a point of contention because somewhere along the way, Levi’s rent money had found its way into Charlie’s bank account, and had yet to confront him about it.

Let’s get something straight. I’m not bothered that you live in a country town and have parents that never have to worry about money. That you had a good education, and study medicine at a swanky university. I’m not fussed that you’re planning a winter skiing trip to St Moritz either. I’m presuming all these things because you speak in an educated manner and are charming with customers, which means that the owner of this cafe is fortunate to have you.

What matters is the present. I’m more interested in my latte and the fact that at any moment you’re going to bring me a pear, stilton, and walnut salad that will be the best I’ve ever tasted. Will I want balsamic or french dressing? I will choose balsamic.

I discovered this cafe years ago. It was cold and dark, the windows steamed up so that you couldn’t see in or out. I returned here two days ago, but now it is August, and the town drowns with too many tourists, but this place is out of sight and a good place to sit and write.

By coincidence, that same winter day I bought Ernest Hemingway’s memoirs at the bookshop next door. A Moveable Feast opens with a chapter called A Good Cafe on the Place-de-Michel, where he sits writing notes in lined notebooks like the ones schoolchildren used in Paris of the 1920s. Inexplicably, he stored them in a Louis Vuitton trunk which he left at the Hotel Ritz in 1928 and forgot about it. The manager reminded him of its existence when he went back in 1956, and he was reunited with his lost scribblings.

I’d look silly, because writing in a notebook is no longer stylish, so I’ve brought my laptop as an excuse. On the way here in the car, I heard a radio programme about people who never completed their work – art, writing, and even needlework. I look at the dozens of stories on my laptop that remain unfinished. I’m reinvigorated to complete them, and you might be responsible, and are the reason I’ve come back.

The other day you were sprawled across a table, scrolling through your phone, and picking at a sandwich. I was perfectly placed to notice that you were handsome. I thought that you were a customer but realised that you worked here and was on an afternoon break. It was enough for me to return and carve a memory that won’t easily be forgotten.

Have I been disappointed? Well, I’ve spotted a few things. That you’re shorter than I imagined but that is fine. There’s that nervous tick that goes almost unnoticed because you hide it with a smile. Then there’s the pale unblemished skin, that expensive haircut and that tiny earring in your left ear.

But it comes down to the pear, stilton, and walnut salad that you bring me, and I think about the gay thing, unless I’ve misread the situation.

It is a bit like my latest story called The World of Bianci, which is about an Italian boy I met on a bus in Verona. This is someone else I didn’t know and whom I also fell in love with.

Spot the problem here?

There is an American psychologist called Robert Sternberg who created the Triangular Theory of Love, which is intimacy, passion, and commitment. Love at first sight is the passion part of this simple hypothesis.

I once read that this may be a sign of something called ‘anxious attachment’ and this sense of attachment increases if I engage in conversation. I couldn’t do this on the bus because I didn’t speak Italian, but here the situation is different. This time it is about your excellent English and talking about lattes and salads and asking me if everything is to my satisfaction.

Infatuation is a terrible thing. That feeling of obsessively intense love, admiration, and the fear that I might never see you again, and that you have spoiled everything because nothing afterwards will come close.

You are on your break again, and on my way out of the cafe, you look up with coleslaw fingers and a mouthful of brie, tomato, and salad leaves, and say thank you.