Sometimes, late at night, Mark messages and asks me what I’m up to. It means that he’s bored and wants somebody to share the boredom with. He’ll pick me up in his purple BMW and we’ll drive into the countryside.

He always drives with one hand on the steering wheel, the other scrolling the touch screen, constantly skipping tracks on Apple Play. The driver’s seat is as far back as it will go because of his long legs, and the seat reclines at an odd angle. He’s not afraid of dark and unfamiliar roads and says it’s safer driving at night. He’ll step on the accelerator and talk about anything, his Yorkshire bluff switching subjects as often as the music. Mostly, I’ll sit in silence.

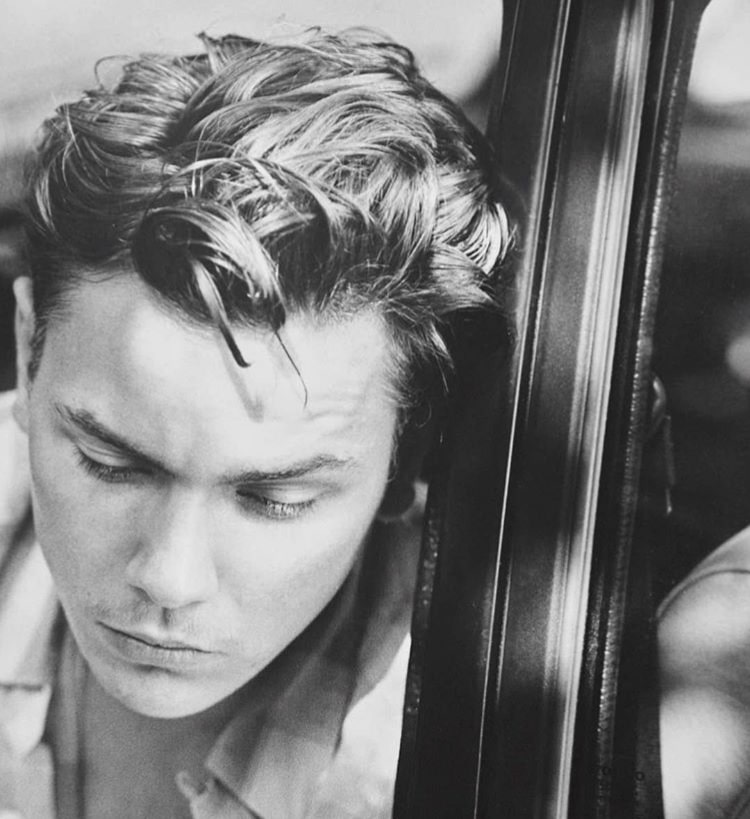

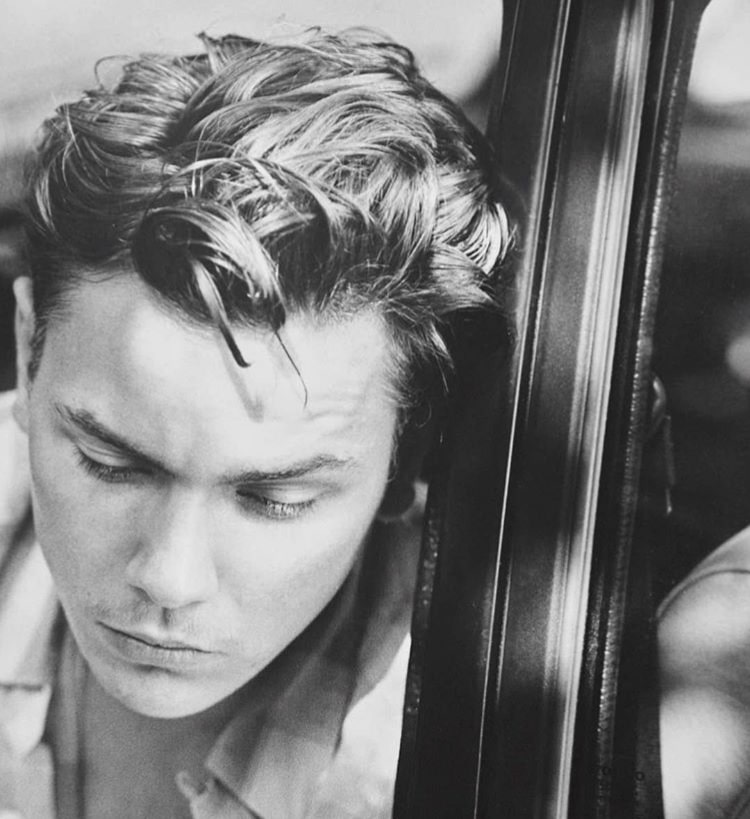

Mark looks like any other lad in his twenties, but I’ve seen through that disarray. The eye can’t see what lies beneath, but I can speculate. With a bit of tidying up, smart haircut, and a good shave, he could be a male model.

I expect that his parents didn’t expect him to be so tall. They are both average height and probably surprised that he outgrew his bed and slept most nights with his feet sticking over the end. He’s over six-foot and lean, not skinny, and certainly not lanky.

In another life, he’d be photographed in his underwear for a glossy magazine and called something like Callum or Luke.

I keep wanting to say this to him, but it sounds pervy and he might think that I’m coming onto him. That’s why I’m mostly quiet.

We’ll drive into the night and might come across an all-night garage where he’ll disappear inside and emerge with arms full of bad things like crisps, chocolate, and cans of Monster.

Then we’ll park in a layby where he’ll switch off the engine so that we’re in complete darkness and demolish it all. He’ll always ask for a cigarette and will get out of the car because he doesn’t want it smelling of smoke, but seemingly oblivious to the empty cans and wrappers that litter the footwells.

We’ll often arrive back in the city during the early hours, say our goodbyes, and I might not see him again for months.

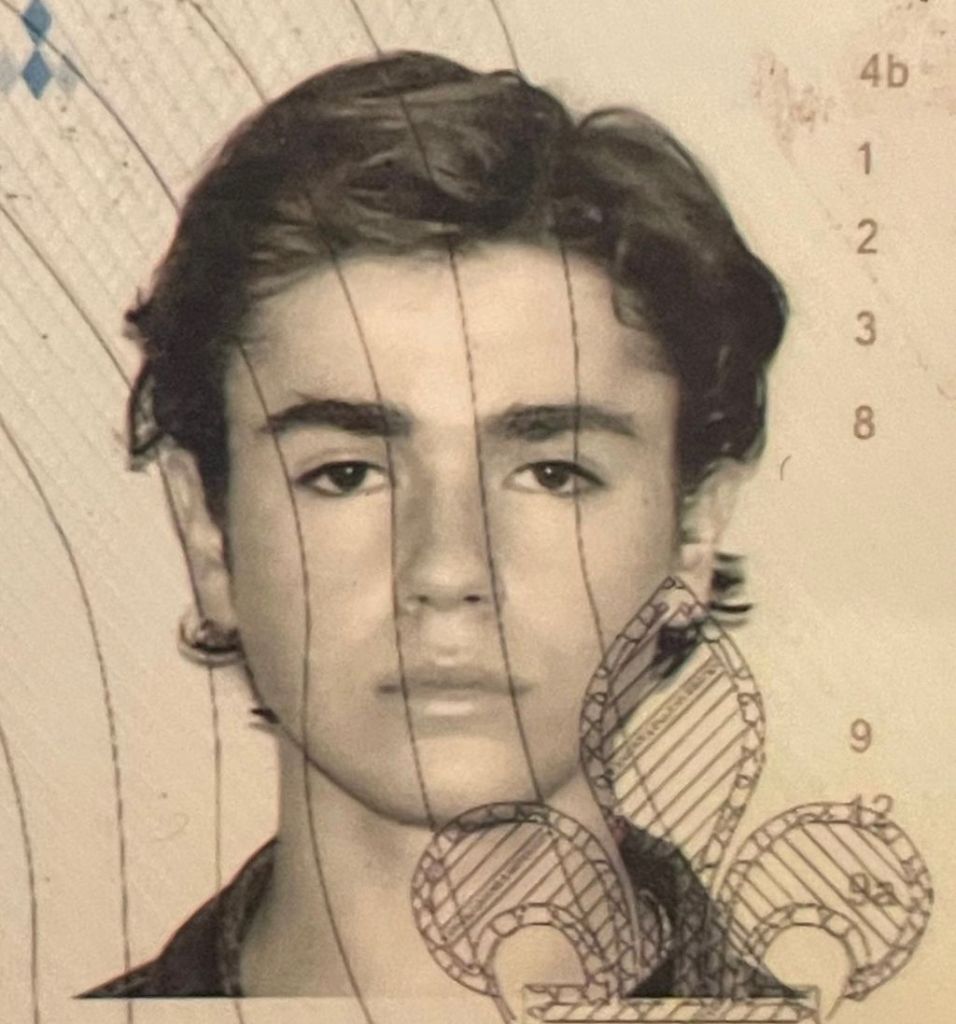

Charlie wasn’t happy when he came back from Barcelona. He didn’t say much on the way from the airport, and I put it down to post holiday blues. He’d spent a lot of time in the sun and was still dressed for the beach.

His arms and legs were tanned, and his thick black hair had ginger tints. He said that he’d had a good time and missed me, but I noticed he was scrolling his phone looking for cheap flights. He was planning a quick return.

I thought about what he might have been up to over the past week. He said he’d met up with friends, but I suspected he’d hooked up with someone. Why else would he be silent? A cute French boy would have no problem finding someone to have sex with. Knowing Charlie, he would have fallen in love with them.

I was resentful but had no reason to be. We weren’t in a relationship and to all extent and purposes we were simply flatmates. Charlie was a flirtatious boy and had carefully manipulated me into letting him have a room.

I’d missed our quiet nights watching movies on TV and missed the hours he spent sitting cross-legged on the floor while he painted.

I had something to tell him, but his gloomy mood suggested it wasn’t the right time.

I was afraid to mention that Levi had moved in.

This was the same Levi, with his boundless energy, who claimed to be Polish and spoke with the broadest Yorkshire accent. Like Charlie, he’d asked for a place to stay, and I’d let him have the spare room.

Charlie sensed something was wrong as soon as we arrived home. I hid in the kitchen while he inspected every corner of the apartment. Eventually he opened the door to the last room and saw Levi asleep on the floor.

Charlie closed the door and muttered something in French that I didn’t understand. Then he threw his rucksack on the floor and kicked off his Nikes. He looked at me, a flash of anger in those eyes that turned to hurt, and he slammed the door as he disappeared into his own room.

It was the first time that I’d seen Charlie jealous, and I felt strangely satisfied.

Bro’, I’m sorry it ended this way. Kayla said I was a pussy. She’s a hard-faced Scouser bitch. She fingered my blue dolphin tattoo and said that I needed to keep face with my boys. I needed to teach you a lesson. I knew that.

It was months ago, and you’d picked up on something that I didn’t want people to see. You’d sent me a message, I was drunk and stupid, and I replied saying that I found you exciting and I was intrigued.

But there was a problem because you showed my message to the boys and made me look a dickhead. Didn’t you think that I wouldn’t find out? That’s why I dropped you because I had to show that I was still the hard cunt I was supposed to be.

I always hold a grudge, and I might have made an exception, until Kayla said the boys were still talking about that message. She said that you didn’t deserve that dolphin tattoo, the one that said that you were in a gang.

Bro’, you must understand that I had to do something about it.

I couldn’t do it myself because I didn’t have the heart, and it was too obvious. Instead, I paid five hundred quid to a geezer from Manchester who was an absolute nutter.

I didn’t know when it would happen, and I bet you thought you were home and dry. But I got you in the end.

I’ve watched it on my mobile phone.

Laying in the gutter on some dark backstreet, snivelling, and begging for mercy. Crying because your nose was split and most of your teeth had gone. Screaming because your face had been slashed with a sharp knife. Blood, blood, everywhere.

When you thought you couldn’t hurt anymore came the kicks and the cracking of bones. There was still unfinished business. Next came the acid that burned your tight stomach and obliterated that badge of honour, the dolphin tattoo.

Somebody will find you, half-dead and alone, and you’ll recover from your wounds, but not your sanity.

Bro’, my boys will know who did it, and they’ll think twice about taking the piss. What can I say? I really did like you, and you excited me, but if I wasn’t going to have that pretty face then nobody would.

The girl I went out with, who thought I was so fucking nice. She couldn’t wait for her parents to meet me because I was perfect. And I’d sit in their little council flat with my arm over their daughter’s shoulders and make polite conversation. We’d watch TV until late into the evening and the brother would stare and not say a word. Dad would offer me cans of Carling and Mum would offer me sandwiches and biscuits until it was time for bed because they had to get up for work.

They’d ask me to stay, not in their daughter’s room, but in the brothers, because he wouldn’t mind me sleeping on his floor. I’d end up stripping down to my boxers and laying on a cheap carpet with a travel rug to keep me warm.

The brother in his single bed would ask me if I’d shagged his sister and I’d say that I had, when I hadn’t. He’d say that it was gross, and then he’d talk football because that’s what lads did, and he’d ask me about movies and music I liked. I’d lay there wishing that he’d shut the fuck up and let me sleep.

But he’d continue to talk, a voice in the dark, asking question after question, until I’d pretend to drop off and he’d say that the floor must be uncomfortable. I’d tell him that I was grateful for somewhere to stay and that I wasn’t bothered. He’d say that it wasn’t right for his sister’s boyfriend to sleep on the floor and that I could have his bed instead.

Eventually, I’d stand shivering in my boxers while he made an Oscar performance getting comfy on the floor. I’d slip into his warm bed with its aromas of Lynx and teenage sweat, and he’d still be chattering.

I’d tell him that I felt guilty about taking his bed and that he could share it if he wanted. He’d say that he wasn’t sharing a bed with another guy because he wasn’t gay, and I’d remind him that I was shagging his sister, and that meant I wasn’t gay either.

He’d crawl into bed and say that it was a bit cramped, and I’d tell him to go to sleep. He’d set an alarm on his mobile phone so he could nip onto the floor before his parents walked in the next morning.

Then he’d ask me if I’d kissed a guy, and I’d lie that I hadn’t. He’d wonder what it would be like, and I’d say that I didn’t know. He’d keep talking until I told him to find a guy to kiss, and then he might shut up. That would mean that he was gay, but he wasn’t.

He’d complain that the bed was too narrow and that he might fall out. When I don’t respond, he’d ask if he can give me a hug and I’d say yes, if that’s what he wanted. He’d put his arm around me, and say that he wasn’t a faggot, and I’d smile.

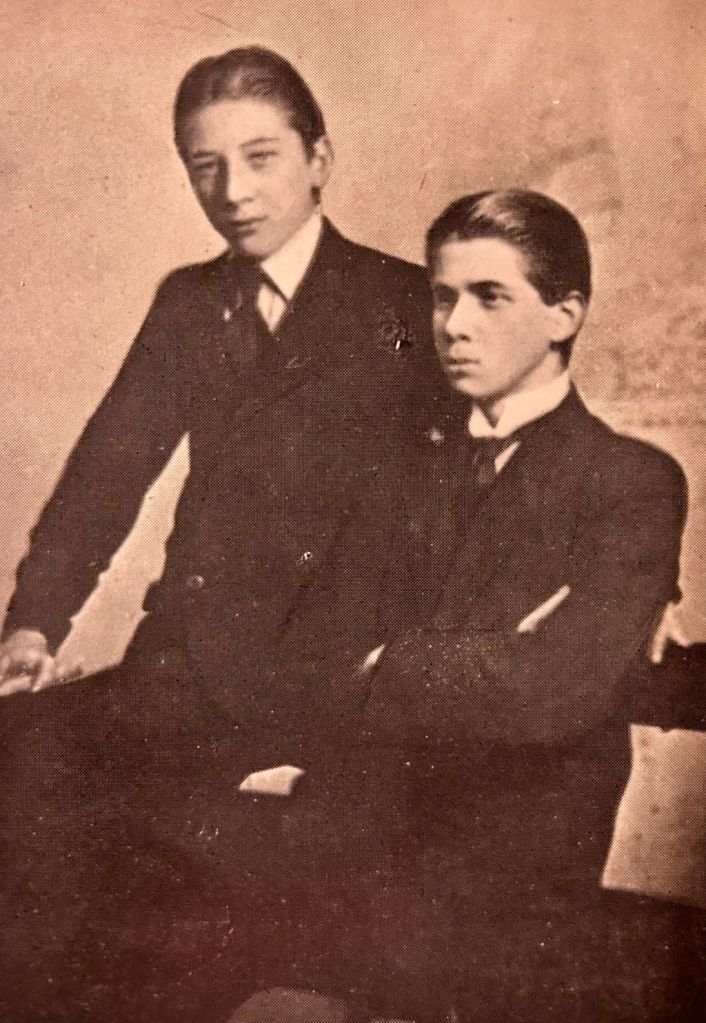

I’m on good terms with William and Julian Percy. We’ve had an intimate relationship these past four years. I was fourteen when I found them. It was a spring day, and I took a shortcut through the cemetery when I wasn’t supposed to. My mother had said it was out of bounds. Bad things happened to boys who wandered here, but she never said what these bad things were. As a child I imagined dead people crawling through the undergrowth, walking amongst graves, hiding behind crumbling monuments, ready to pounce on little boys. As I got older, I realised it wasn’t the dead that I needed to be afraid of, but the living.

I’ve come to believe that William and Julian called me that day. Voices from beyond urging me to leave the rough path and clamber over graves and through waist-deep brambles and nettles until I was lost. The sun shone and birds sang a ripe chorus. Amidst this secrecy was the long forgotten grave of William and Julian Percy who beckoned me to sit on the warmth of their heated stone.

I read the carved inscription: –

Here lies William Percy 1900 – 1918. Also, Julian Percy 1901 – 1918

“The sorrow we felt we cannot explain,

The ache in our hearts

Will always remain.”

I realised that they had been brothers, but only recently did I understand that they had been victims of that Great War.

I used to think that their bodies lay side by side, but the narrow tomb wouldn’t have allowed that. They were undoubtedly on top of each other, their brotherly bodies had rotted until they became one, their skeletal remains intwined.

These boys had been loved, mourned, and eventually forgotten. Nature had claimed their bodies as well as their final resting place.

The grave had sunk, and small holes had appeared where the stone had shifted. I peered into the blackness hoping to see something. I reached inside but they were merely hollows where I would later hide cans of Stella and packets of Marlboro Gold.

I came here daily and talked to William and Julian. I shared my secrets and thoughts, and told them about my small world. They always spoke back to me.

They didn’t mind me coming because they liked me and I they.

I don’t see them as skeletons anymore. They are handsome young boys who gave their lives for their country. They remain out of sight during the day, waiting for me to visit, and when darkness falls and owls call from the trees, they come out and roam amongst their friends.

They were musical. William played the cornet and Julian was expert at the violin, and their instruments were buried with them. Was this true? I like to think so. I’ve played them the music I listen to – Bring Me the Horizon, YUNGBLUD and The Reytons – and they smile at the Yorkshire accents because it reminds them of people they once knew.

They didn’t mind that long hot summer when I sunbathed naked on top of them and drank a full bottle of wine I’d stolen from the corner shop and fell asleep until I burned red.

They liked it when I read the opening paragraph of a cool book I found in Oxfam.

“Last night, I fell out with Amy when she caught me sucking her boyfriend under the table of some stinking Euro-pop club in not so gay Paris. She’d been going out with him for five days and claimed he was straight. But as soon as I clocked how much eyeliner he had on, I told her the only place he was going was straight to a gay bar.”

They’d both laughed and made me recite the whole book over the next few days.

Today, they want to have a serious conversation.

“We’ve really enjoyed your visits,” said William.

“It’s been lovely to talk to someone after a hundred years,” interrupted Julian.

“Yes,” said William, “But the time has come when you will no longer be able to come and talk to us.”

“What do you mean?”

“What we’re saying,” said Julian, “is that today is the anniversary of our deaths, and we realise that we might have misled you into thinking that we were soldiers who died at war.”

“But that wasn’t the case,” said William. “Yes, we both served our country and were scarred but came home unharmed.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Remember when you came to us a few years ago and spoke about a pandemic and you were forced to stay at home for months?”

“Lockdown,” I agreed.

“But you still came to see us every day,” Julian commented, “And we didn’t feel it was the right time to tell you the truth about how we died.”

“How did you die?”

“Well,” continued William, “we both died of influenza, a dreadful disease that one of us picked up in France.”

“The Spanish flu?”

“That’s what they called it,” said Julian, “and it was an unpleasant experience that turned into pneumonia, and ultimately our deaths.”

“Julian got it first and I sat beside his bed while he slipped away, and then I became ill and by the end of the day had surrendered to it as well. We had each other, but our parents were heartbroken.”

“You see why we didn’t want to frighten you before?” asked Julian.

“That’s so sad,” I told them, “But I’ll keep visiting.”

“Yes, you can visit, and I hope that you shall, but I’m afraid that we won’t be able to speak with you.”

“Whyever not?”

“As the oldest, I was eighteen years old when I died. How old are you now?”

“I’m eighteen, almost nineteen.”

“And come tomorrow you will have lived a longer life than I did, and that means that our ability to talk must come to an end.”

“But what about Julian? He was only seventeen.”

“Alas,” said Julian, “Brothers must stick together in life and in death and where my brother goes, I shall follow.”

“You’re both leaving?”

“We move on, somewhere else, but we shall occasionally return to see our final home. And you shall get on with your own life and in time will forget we ever existed.”

I left the cemetery. Angry, dejected, and sad. I never even said goodbe. And, as I crawled through the familiar undergrowth, the day darkened and spots of rain started to fall, and I swear that I could hear a tune somewhere behind me. It was played by a mournful trumpet and a sorrowful violin.

The boys with the bling. In you came, with your coloured VKs and a hint of nervousness in those childlike eyes. I watched because you might have been young lovers.

There are two personalities here. The one who likes to show off, and the sweet one who is content to sit and watch him.

The smaller boy dances, puffs on a vape, and makes ‘v’ signs to some gangster shit. His unobtrusive friend is made to take videos of him that will end up on Tik Tok. Then the extrovert shouts “Newcastle!” in a voice that cracks, and then I realise that the Magpies have stuck eight goals past United.

These are the boys.

The last of the many who celebrated into the night and one by one, they fell away, drunk, bleary-eyed, until only these two Geordie Angels remained.

Enthusiastic boys, unaware that they are being watched from a distance.

Energetic boys who don’t appreciate the luck they are blessed with.

Passionate boys who are not like the persona they project.

Naughty boys who talk like gangstas but are deep-down sensitive.

Fashionable boys with silver threads around their necks, who dress like they think they should, and not how they they would like to. Moschino, Hoodrich, North face, Stone Island.

Boys who stuff their hands down their underwear because they think it makes them hard. Boys who pretend their sweet smelling piss and cum fingers are guns.

Handsome boys who don’t understand that they are ancestral sons of Adonis who grew up on our council estates.

Boys who like boys, but must like girls, who are always fat girls.

We are envious, and we weep at the unfairness of it all.

There was a time not so long ago when I was alone. The apartment was mine only. It is big and lonely, not that I spend much time in it, but it’s a place where I can retreat.

That was also a time when I had more money. It’s easy to save money when you are living alone.

That changed the day Charlie from Paris arrived in his old Austin car. He needed somewhere to stay for a few weeks and everyone thought my big apartment was the solution.

I agreed and I gave him a room and bed, a door key, and the run of the place. Charlie liked it, and it was soon apparent that he had no intention of leaving.

A van appeared one sunny morning and a man said he’d got several boxes for me. Not for me, you understand. There were about fifteen neatly packaged crates, each containing books, DVDs, vinyl records, and lots of clothes.

Charlie spent hours unpacking his possessions and carefully placing them around his room.

The following week more boxes arrived containing canvases, paint brushes, sketch pads and more clothes.

Charlie had moved in, and I didn’t really mind.

“This apartment has character,’ he said. It does have a charm about it but he’s never offered to pay for his stay. Nor does he pay for the food that he eats.

Charlie’s way of saying thank you is to offer small gifts. A poem he’s written, a picture he’s painted and sometimes a book he’s seen and knows I will like.

It’s all quite nice really.

‘We are like a couple,” he once joked. Except that we aren’t because I continue my liaisons with other men, and Charlie keeps disappearing to London and Paris to visit galleries. I never ask him what else he gets up to.

He always comes back.

Most people think we are a couple, and that is a nice thought. They think our nights consist of sharing a bed and being lovers. We aren’t, but I’d like to think that one day we might be.

Am I jealous of Charlie? I’m beginning to realise that I am.

He’s announced that he’s going to Barcelona for a week in September. He showed me photos of the hotel he’s staying in. The Monument Hotel. Four stars and all that. I asked him how much it was costing and he said it was only €800 which sounded a lot. I checked out how much that would be in English pounds and it came to £700 which still sounded a lot.

“You don’t mind me going away?” Charlie asked.”I need a holiday.”

I wanted to say that I did mind. That I would like to go with him. That I need a holiday more than he does. That he can afford to go because he’s living for free. That I can’t afford to go because I pay for everything.

I said none of these things.

“It sounds wonderful,” I said. “I hope you have a lovely time.”