I remembered a room. It was a room I’d forgotten about, but one I once loved. And I reminisced because I heard a song by Arctic Monkeys called There’d Better Be a Mirrorball.

“So can we please be absolutely sure that there’s a mirrorball.”

This room had been in a big Victorian house, the kind that might have been built for a wealthy industrialist, a doctor, or a prosperous shopkeeper.

This house was now home to my best mate Jimmy whose family had removed old fancies and squeezed its offspring into every nook and cranny. He slept with his brother in the attic where God-faring servants had once lived.

This special room, the one I suddenly remembered, was downstairs, and there must have been a window, but I cannot recall ever seeing one. It wasn’t a large room; it would have once been the dining room, but now the family ate at the kitchen table.

Once upon a time, a piano might have stood against the wall, Henry Hall records might have been played on a phonogram, and where a frightened family might have listened to the wireless while bombs exploded in the valley below.

That was all in the past.

A snooker table stood where a polished dining table had been, a table with matching carved chairs, and where grace would have been spoken before each meal. But I never saw a game of snooker played.

Above it, the chandelier had been swapped for that evocative mirrorball, onto which disco lights shone and cast a cataclysm of colour around the room and into every corner. It was bright and beautiful, but when the party stopped, you might have called it a dark and gloomy room.

Most fascinating were its walls and ceiling; the arsenic flavoured Lincrusta had gone, the over-elaborate plasterwork had survived, but now painted in a garish colour.

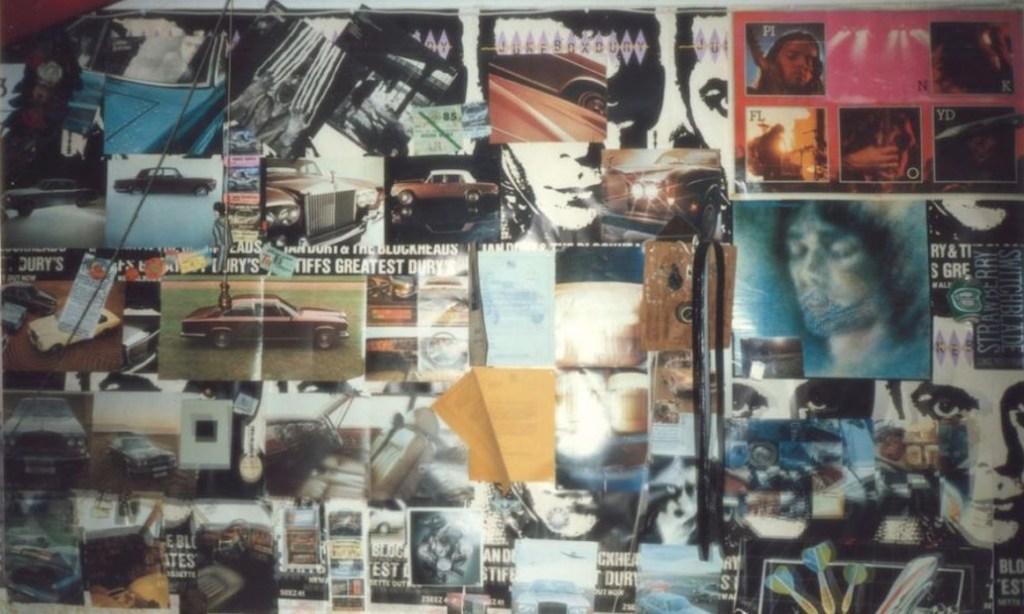

But this was a room where you read the walls; every inch had been covered in poster pin-ups, glossy magazine pages, picture record sleeves, and mementos from summer holidays. The transformation had begun in the seventies, and the eighties had introduced New Romantics to Punks.

And music thundered from a costly hi-fi system: Bananarama, Fun Boy Three, Spandau Ballet, Culture Club, Dexy’s Midnight Runners (always Come On, Eileen) and boy pin-ups like Paul Young, Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw. I don’t remember seeing any girls.

In mind’s eye, I am sober while looking at this room, but I never really saw it when I wasn’t drunk. Because it was to this house that we came when Broomhill’s pubs had closed, and where Jimmy’s family gathered, where cousins and friends migrated, and fortunate neighbours called late on Saturday night. It was where your glass was never empty, always topped up with indescribable spirits from the continent.

And the parties flowed from room to room, but it was in the shadows of the mirrorball where youngsters gathered. We sat on a battered old sofa that would be worth thousands now, or on mismatched armchairs with their stuffing hanging out. We spilt drinks on the green baize and listened to records that Jimmy had bought, the sleeves quickly discarded, because he’d stuck them to the wall with Sellotape.

But we never smoked and didn’t take drugs.

In the early hours of the morning, when most on this stylish street were asleep, the gathering would dwindle, but not before its guests took an age to leave. And Jimmy’s mother, called Enid, would tell me to stay the night.

I slept in my boxer shorts in one of three single beds in that attic. It was the bed in the middle because Jimmy and his older brother, John, who was partly deaf, slept either side, and I would lay thinking that I was in love with both.

The next day I was always first up, and in the same clothes I wore the night before, I would go down to the kitchen where Enid was preparing Sunday dinner and she’d make me a mug of tea and ask me to stay because she knew I loved her onion sauce.

Like the sorrowful tone of that Arctic Monkeys song, it came to an end, and that’s probably why I thought of that room and its mirrorball.

I also think of a sour-faced girl, who also fell in love with Jimmy, and stole him away. She once looked at me and her expression said, “I won, you lost.”

“Don’t get emotional, that ain’t like you. Yesterday still leaking through the roof. But that’s nothing new.”