The first time Brodie and Archie met was not under the best of circumstances.

It was a Friday afternoon beneath the Miller Theatre on West 51st Street. Brodie – hi-viz vest zipped to the throat – stood amid abandoned scaffolding, photographing stress fractures in the concrete. The air was dense with dust, old and mineral, as though the building itself were exhaling.

A figure emerged at the far end of the tunnel and walked towards him.

Brodie lowered the camera. He waited until the young man was close enough to see properly, then snapped, “What are you doing here? This is a restricted area. Turn around and go back the way you came.”

“I’m sorry,” the young man said. He spoke with an English accent, careful, almost courteous. “I didn’t realise. What was this tunnel used for?”

“The other side of that wall is backstage,” Brodie replied. “Probably for actors crossing beneath the stage. But there’s no time for questions. It’s unsafe down here. The roof could come down at any moment.”

It was an exaggeration. But saying it gave him a small, illicit thrill – authority borrowed from the place.

The young man hesitated. He had floppy brown hair, eyes dark and inquisitive despite the rebuke. “What are you doing?”

“I’m inspecting the structure,” Brodie said. “Everything looks glitzy up there. Down here it’s rot and age.” He paused. “You still haven’t explained why you’re trespassing.”

“I was just exploring.”

“Explore somewhere else.”

The young man’s shoulders dropped. As he turned, he fumbled the folder under his arm; papers spilled across the dusty floor.

“Shit – sorry. My script.”

Something softened in Brodie then, too late to retract the sharpness he’d already spent.

The second time they met was in the staffroom.

Brodie was entering notes on his laptop when the door burst open and a tide of people flooded in, loud with laughter, trailing the smell of coffee and citrus wipes. Lunch packs appeared: protein bars, yogurt, hummus, cut vegetables. Actors, Brodie thought, irritated beyond reason.

Michael wanted renovation proposals by Monday. Concentration felt impossible.

Then he saw him – the boy from the tunnel – laughing with the others, sleeves pushed up, script tucked under his arm as if it were a talisman.

Of course.

On their way out, the young man stopped at Brodie’s table. “I’m Archie,” he said, holding out his hand. His eyes lingered, dark and unguarded. “I think we got off on the wrong foot.”

Brodie hesitated, then took it. The contact was brief, oddly charged. “I’m Brodie. Forget about it. Just – stay out of the tunnel.”

Archie smiled, chastened and amused all at once.

After that, Brodie thought about him more than he liked to admit.

He knew he could be abrupt, inflated by his own sense of usefulness. Actors irritated him on principle. But Archie – English, polite, quietly intense – had unsettled him.

Late one night, Brodie searched the Playbill bios. Archie was a rising star: television work, the National Theatre, lead roles in the West End, now a Broadway debut.

Impressive.

What Brodie didn’t know was that Archie had been searching too. He’d asked about the surveys, about the renovation. He found the company. He found Brodie’s photograph.

Hazel eyes. Skin warm-toned, as if lit from inside. A face shaped by movement rather than posing.

Tasty, Archie thought, surprised by his own boldness.

Two years later.

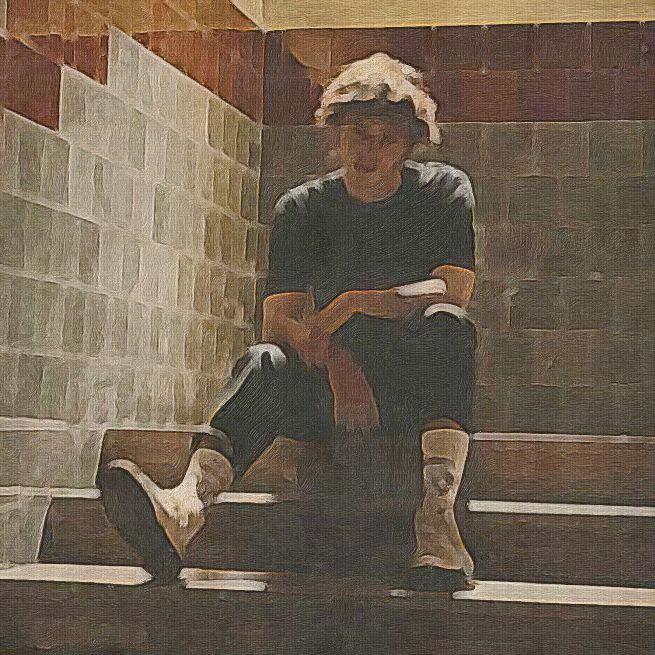

Archie slipped out of the Walter Kerr Theatre the moment the curtain fell on Chatterton. No shower. No linger. Wool coat, beanie, scarf pulled high. He moved fast, before the autograph hunters gathered.

Outside, Broadway surged and glittered – yellow cabs, steam vents, neon, voices colliding. It still thrilled him. It always did. A world away from Buckinghamshire.

At the apartment, Brodie checked the clock: 10:30. Any minute now.

The flowers were arranged just so. Archie liked flowers. Brodie liked that Archie liked them.

When the door opened, relief moved through him like a current.

Tea was requested. Always tea. Archie shed the night – coat, scarf, public self – and collapsed onto the sofa. He spoke about the show, about the line he’d missed. Brodie stroked his hair, grounding him.

Later, Fleet Foxes floated from the bathroom. Steam curled beneath the door.

Brodie knew the routine by heart. He would collect the clothes, note the forgotten boxers, breathe in the faint, intimate salt of them – something human beneath the polish. It embarrassed him how much that scent moved him.

Archie emerged clean and fragrant: Le Labo, Dior and mint. Blue silk pyjamas. He smiled like someone stepping into safety.

They ate together. They watched television under the blanket Archie’s grandmother had made. Archie pressed close, smaller than he seemed onstage, all softness and thoughtfulness and unspoken worry.

Sometimes Brodie felt the weight of what he was not allowed to be – unseen, untagged, absent from photographs. Invisible by design. But here, in this private room, their bodies fit without explanation. The most erotic moments were those that could not be shared publicly.

Brodie was Archie’s shelter. Archie was Brodie’s undoing.

Brodie had watched hundreds of videos of Archie on YouTube, moments in which he appeared entirely at ease – charming interviewers, holding eye contact, listening with an attentiveness that felt generous rather than rehearsed.

His answers were always articulate, delivered with that unmistakable smile. But Brodie could see what others missed.

The exposure beneath the polish. The small betrayals of nerves: the way Archie’s smile lingered a fraction too long; the absent-minded stroking of his own arm as he spoke; the slow, circular massaging of each finger; the hand lifting to his hair, not to adjust it, but to reassure himself it was still there.

These gestures were invisible to the audience, but to Brodie they were intimate, almost confessional – proof that the confidence was something Archie stepped into, not something he owned.

Thomas Chatterton had been an ideal role for Archie. The eighteenth-century poet – celebrated as the marvellous boy for his precocious brilliance and dead at seventeen – had been reimagined as the subject of a hugely successful Broadway musical.

In his twenties, Archie might once have been considered too old for the part, but his fine, boyish beauty dissolved any such doubt. Night after night, he stepped into Chatterton with such ease that the distinction between role and actor began to blur.

To the audience, he seemed timeless, suspended in youth and promise. To Brodie, there was something quietly unsettling in this devotion – the way Archie gave himself over to a boy who never lived long enough to be disappointed by what came after.

When the movie ended, the future rose between them.

“Would you come to London?” Archie asked quietly.

Brodie had been waiting for this. “Yes. If you ask me to.”

Archie’s eyes filled. “You’ll have to share me.”

Brodie pulled him closer. “I already do.”