I’m on good terms with William and Julian Percy. We’ve had an intimate relationship these past four years. I was fourteen when I found them. It was a spring day, and I took a shortcut through the cemetery when I wasn’t supposed to. My mother had said it was out of bounds. Bad things happened to boys who wandered here, but she never said what these bad things were. As a child I imagined dead people crawling through the undergrowth, walking amongst graves, hiding behind crumbling monuments, ready to pounce on little boys. As I got older, I realised it wasn’t the dead that I needed to be afraid of, but the living.

I’ve come to believe that William and Julian called me that day. Voices from beyond urging me to leave the rough path and clamber over graves and through waist-deep brambles and nettles until I was lost. The sun shone and birds sang a ripe chorus. Amidst this secrecy was the long forgotten grave of William and Julian Percy who beckoned me to sit on the warmth of their heated stone.

I read the carved inscription: –

Here lies William Percy 1900 – 1918. Also, Julian Percy 1901 – 1918

“The sorrow we felt we cannot explain,

The ache in our hearts

Will always remain.”

I realised that they had been brothers, but only recently did I understand that they had been victims of that Great War.

I used to think that their bodies lay side by side, but the narrow tomb wouldn’t have allowed that. They were undoubtedly on top of each other, their brotherly bodies had rotted until they became one, their skeletal remains intwined.

These boys had been loved, mourned, and eventually forgotten. Nature had claimed their bodies as well as their final resting place.

The grave had sunk, and small holes had appeared where the stone had shifted. I peered into the blackness hoping to see something. I reached inside but they were merely hollows where I would later hide cans of Stella and packets of Marlboro Gold.

I came here daily and talked to William and Julian. I shared my secrets and thoughts, and told them about my small world. They always spoke back to me.

They didn’t mind me coming because they liked me and I they.

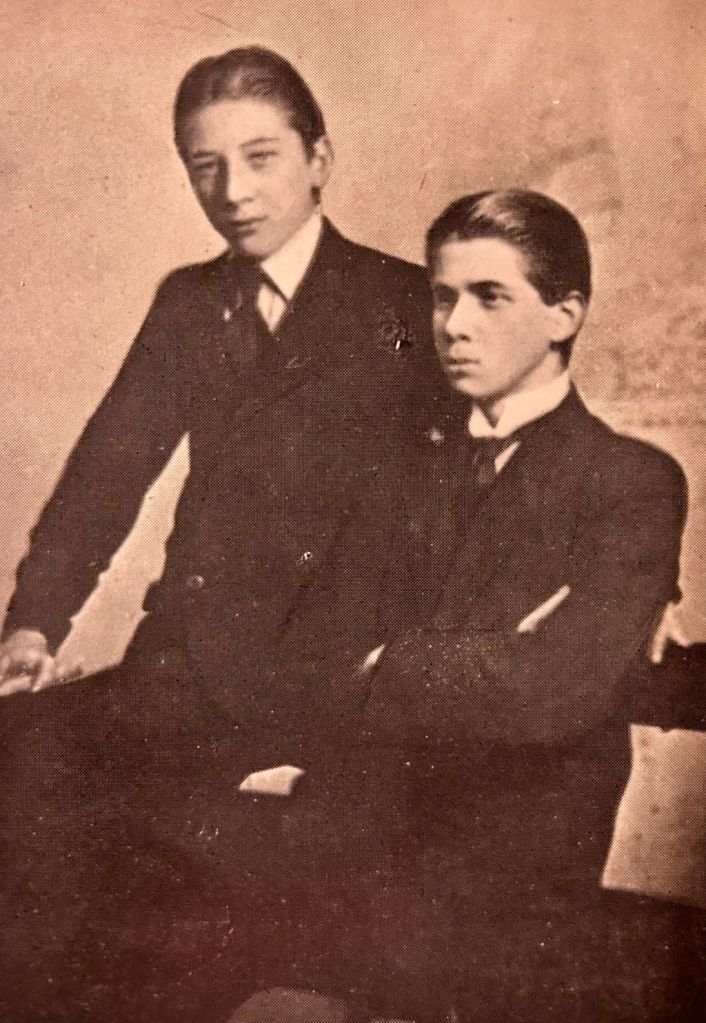

I don’t see them as skeletons anymore. They are handsome young boys who gave their lives for their country. They remain out of sight during the day, waiting for me to visit, and when darkness falls and owls call from the trees, they come out and roam amongst their friends.

They were musical. William played the cornet and Julian was expert at the violin, and their instruments were buried with them. Was this true? I like to think so. I’ve played them the music I listen to – Bring Me the Horizon, YUNGBLUD and The Reytons – and they smile at the Yorkshire accents because it reminds them of people they once knew.

They didn’t mind that long hot summer when I sunbathed naked on top of them and drank a full bottle of wine I’d stolen from the corner shop and fell asleep until I burned red.

They liked it when I read the opening paragraph of a cool book I found in Oxfam.

“Last night, I fell out with Amy when she caught me sucking her boyfriend under the table of some stinking Euro-pop club in not so gay Paris. She’d been going out with him for five days and claimed he was straight. But as soon as I clocked how much eyeliner he had on, I told her the only place he was going was straight to a gay bar.”

They’d both laughed and made me recite the whole book over the next few days.

Today, they want to have a serious conversation.

“We’ve really enjoyed your visits,” said William.

“It’s been lovely to talk to someone after a hundred years,” interrupted Julian.

“Yes,” said William, “But the time has come when you will no longer be able to come and talk to us.”

“What do you mean?”

“What we’re saying,” said Julian, “is that today is the anniversary of our deaths, and we realise that we might have misled you into thinking that we were soldiers who died at war.”

“But that wasn’t the case,” said William. “Yes, we both served our country and were scarred but came home unharmed.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Remember when you came to us a few years ago and spoke about a pandemic and you were forced to stay at home for months?”

“Lockdown,” I agreed.

“But you still came to see us every day,” Julian commented, “And we didn’t feel it was the right time to tell you the truth about how we died.”

“How did you die?”

“Well,” continued William, “we both died of influenza, a dreadful disease that one of us picked up in France.”

“The Spanish flu?”

“That’s what they called it,” said Julian, “and it was an unpleasant experience that turned into pneumonia, and ultimately our deaths.”

“Julian got it first and I sat beside his bed while he slipped away, and then I became ill and by the end of the day had surrendered to it as well. We had each other, but our parents were heartbroken.”

“You see why we didn’t want to frighten you before?” asked Julian.

“That’s so sad,” I told them, “But I’ll keep visiting.”

“Yes, you can visit, and I hope that you shall, but I’m afraid that we won’t be able to speak with you.”

“Whyever not?”

“As the oldest, I was eighteen years old when I died. How old are you now?”

“I’m eighteen, almost nineteen.”

“And come tomorrow you will have lived a longer life than I did, and that means that our ability to talk must come to an end.”

“But what about Julian? He was only seventeen.”

“Alas,” said Julian, “Brothers must stick together in life and in death and where my brother goes, I shall follow.”

“You’re both leaving?”

“We move on, somewhere else, but we shall occasionally return to see our final home. And you shall get on with your own life and in time will forget we ever existed.”

I left the cemetery. Angry, dejected, and sad. I never even said goodbe. And, as I crawled through the familiar undergrowth, the day darkened and spots of rain started to fall, and I swear that I could hear a tune somewhere behind me. It was played by a mournful trumpet and a sorrowful violin.