My friend David is reading a biography of the writer Christopher Isherwood on his Kindle. It has taken him a long time to get through—not because the book is difficult, but because it is extremely long. He joked that his Kindle had travelled with him from London to Munich and Paris, and back again, and he had only reached the fifty-percent mark.

“That’s the problem with an e-book,” he said. “We don’t talk about pages anymore. We obsess over percentages.”

I suggested that perhaps he was in too much of a hurry to finish it.

“That’s true,” he reflected, “but don’t you always have one eye on what you’re going to read next?”

David is a lot older than me, and I’m not entirely sure where we first met. He is educated, though—one of those men whose words are almost always guaranteed to entertain. We were walking beside the canal from Paddington Station towards Little Venice. It was dark, lonely, and faintly threatening. I half-expected a knife-wielding mugger to emerge from the shadows at any moment.

For someone like me, who comes from the provinces, London can feel dangerous. David had no such concerns. He regarded nighttime as the best time to wander its quieter streets, harvesting inspiration for his novels, though on this occasion he had also had to tolerate my repeated complaints.

He tried to change the subject.

“The other day I went into Daunt Books on Marylebone High Street,” he said, “and overheard two older women talking. One of them said, There are so many books to read, and so little time left to do it. That made me think about my own mortality. It’s probably why I’m in such a hurry to finish the Isherwood biography.”

It was the first time I’d heard him refer to his age in that way. I’d never really considered that it might trouble him.

It was my turn to change the subject.

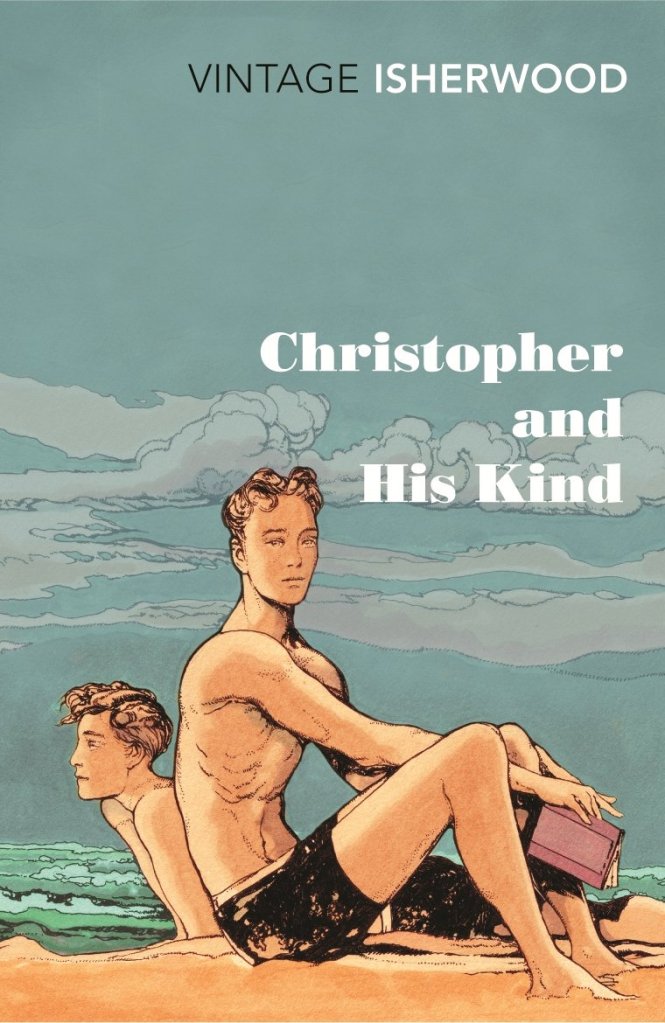

“To be honest, I’ve never read Isherwood,” I said. “I find him a bit of a privileged bore.”

He seemed not to hear me.

“There are several comparisons between Isherwood and myself,” he continued. “I’ve been struggling to come up with new ideas recently, and while reading the biography I came across a quote from his diaries: A lack of creative inclination to cope with a constructed, invented plot—the feeling, why not write what one experiences from day to day? Why invent, when life is so prodigious?”

He paused, as if letting the words settle.

“That resonated with me. I’ve decided that my future writing will only be based on real life experiences. That will be far more satisfying.”

David’s work had always relied on a radiant imagination—several bestsellers proved that—but this declaration unsettled me. As if anticipating my concern, he smiled.

“I have a lifetime of fascinating stories involving my closest friends,” he said. “Some of them might raise a few eyebrows.”

“Did Isherwood do as he suggested?” I asked.

“Absolutely. He created characters based on people he knew. Sometimes he even wrote about himself in the third person, omniscient. I plan to do the same. I’ll call my character David—and absolve myself of any blame.”

We passed moored canal barges. Most were dark, but a few glowed from within: a man cooking over a tiny stove, a woman bent over her laptop, someone stretched out watching television. Their lives were visible through brightly lit portholes, as if privacy were optional.

“There are other similarities between Isherwood and me,” David went on. “When he was forty-eight he met his long-term partner, who was only eighteen. Does that sound familiar? Joshua was twenty-one when I met him. I was forty-four. Seventeen years later, we’re still together.”

“To be honest,” I said, “I’m surprised your relationship has lasted this long.”

I thought of the times he had propositioned me, and of the occasions I had refused him. I would have been eight when he met Joshua, who was now approaching forty. I had been in my early twenties when I first met David.

“The secret,” he said, “is not to make a relationship exclusive. Not my words—Isherwood’s. He and Don Bachardy both had sex with other people.”

It sounded close to a confession.

“Young men enjoy the benefits of being with an older man,” he continued. “Even if they get their sex elsewhere. Boys can take on the identity of their mentor. Bachardy picked up Isherwood’s accent within a year. Joshua is still his own person, but he always comes home. He values stability.”

Above us, traffic thundered along the Westway flyover. Sirens cut through the night. London had become a city of constant alarm. We were nearing Little Venice—named, supposedly, by Lord Byron, who compared its rubbish-filled waters to the Italian city he had once lived in. In the darkness we could just make out Browning’s Island.

“This is where Paddington Bear was once carried by a swan,” David joked. “Though I suppose that means nothing to you.”

My mind was elsewhere.

“I know times were different,” I said, “but Isherwood might today be accused of grooming a young boy.”

“I knew you’d say that,” David replied. “And yes—you’re right. An established literary figure and a college freshman. There were even unkind rumours in New York that he was with a twelve-year-old. His friends disliked Bachardy. But they turned a moral weakness into a long-term relationship. Rather like Joshua and me.”

He paused.

“Back then, people were blissfully unaware. Today everything is played out before a global audience. If the same thing happened now, Isherwood would be cancelled—even if nothing illegal had occurred. We used to call it boy-love. An appreciation of male beauty going back to the Greeks and Romans. Now it’s considered dirty. That’s something I struggle with.”

A person with limited education is at a disadvantage when arguing with David. He always has the clever words ready. My clumsiness betrayed me.

“Can’t you see that there’s something disgusting about the age difference?”

He frowned—not so much at my disapproval, but at my inelegance.

“When I was young,” he said, “homosexuality wasn’t acceptable. Many of us missed out on young love. Then the AIDS crisis came. Now we grow old resentful, because there’s a void. Is it so terrible that we try to recover something we lost? You’re the generation without constraint. You don’t understand our predicament.”

He stopped walking.

“No matter how old you are,” he said, “there will always be something exquisite about youth.”

“Why?” I asked. “Isherwood came from an even older generation. And what you’re saying sounds pederastic to people my age.”

“When Isherwood was young in the 1920s, he was driven out of Germany by the Nazis. Berlin became dangerous. By the time Bachardy appeared, Isherwood was already considered ancient. Some say the boy did the chasing. The relationship later became non-sexual. Bachardy had other lovers.”

A group of students approached—three boys, two girls—laughing loudly before falling into an awkward silence as they passed us. I recognised the look. Suspicion. Not for the first time, I’d been mistaken for a male hooker. I resisted the urge to run after them and explain myself.

David smirked.

“I think I know why you struggle with age disparity,” he said. “That look on your face—it wasn’t moral outrage. It was embarrassment. Shame. You’re ashamed to be seen with someone older.”

He shook his head.

“That’s not a virtue I admire. One day you’ll find yourself old without warning. And the object of your desire will be much younger. I hope that boy doesn’t think the way you do now.”