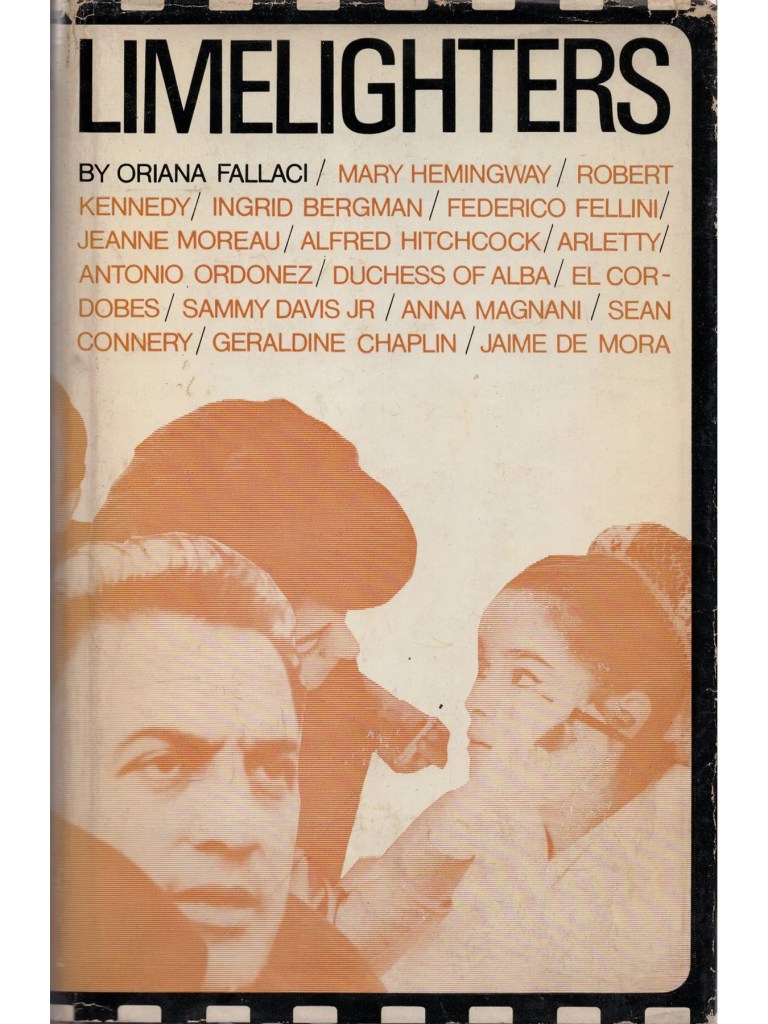

The night was still young as I sat quietly on the terrace, immersed in a book I had recently purchased from a second-hand bookstore back home. The book in question was an English translation of Oriana Fallaci’s work, originally titled Gli Antipatici and published in 1963. My edition bore the name Limelighters, and the author had thoughtfully explained that the Italian title did not lend itself to an easy English translation. According to Fallaci, “When Italians say antipatico, antipatici in the plural, they mean someone that they dislike on sight, and so if I was forced to choose a translation for antipatico, I would say unlikeable.” This explanation, rather than clarifying matters for me, added to my confusion, especially as I struggled to grasp Italian nuances.

The book is a collection of interviews with notable personalities; all recorded for the Rome newspaper L’Europeo using a portable tape-recorder. It begins with the line, “Many of the characters who figure in this book are my friends.” Fallaci proceeds to write friendly and insightful pieces about the stars of her era, including Bergman, Fellini, Hitchcock, and Connery. My bewilderment stemmed from the apparent contradiction between the book’s title and the content, which was anything but unlikeable in its tone and approach.

Most of the fifteen personalities featured in the book, along with Fallaci herself, have since passed away. The chapter that resonated most with me focused on El Cordobés, the Spanish matador and actor, who was still alive. Fallaci masterfully depicted his wild lifestyle: “he buys lined and squared exercise books, but then leaves them blank,” a habit I found relatable. She described him as being constantly surrounded by an eclectic group—banderilleros, priests, lawyers, in-laws, guitarists, boys from his cuadrilla, photographers, chauffeurs, Frenchmen intent on writing his biography, and a brunette whom he had just picked up in Granada. By tomorrow, he would have grown tired of her, and another would take her place. El Cordobés’s story captivated me; I imagined myself as one of the jealous boys from his cuadrilla.

At around seven o’clock, Cola called and mentioned that he was taking Cinzia to see a film, asking if I would like to join them. I declined, but he persisted, suggesting that my presence might encourage Cinzia’s younger brother to come along. “Bel ragazzo,” he confided with a wink.

Wearing an Inter football shirt, he showed little urgency in leaving and spent time browsing magazines before casually flicking through the international edition of the New York Times, which failed to capture his interest.

Cola never displayed any reservations about my homosexuality, even though I had kept this aspect of my life hidden from him when he was younger. I recall being invited to dinner by Signora Bruschi when Cola was about fifteen. After we had finished our Bistecca alla fiorentina, Cola rested his chin in his hands and, with the innocence of a choirboy, asked, “Is it true that you like to fuck boys?”